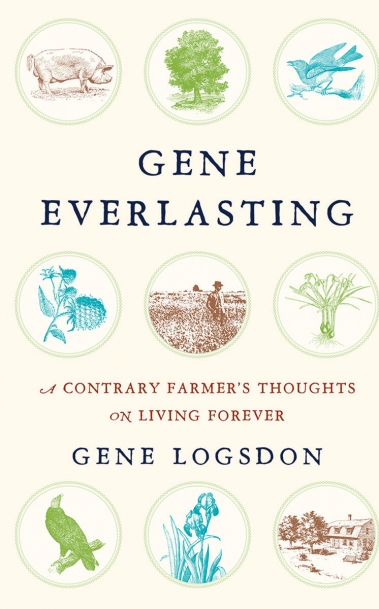

Garden Therapy Along with Chemotherapy

From the book Gene Everlasting

I have a notion that it is a little easier for gardeners and farmers to accept death than the rest of the populace. Every day we help plants and animals begin life and help plants and animals end life. We are acculturated to the food chain. We understand how all living things are seated around a dining table, eating while being eaten. We realize that all of nature is in flux. I work in all seasons on a strawberry patch that for only three weeks produces fruit. All year Carol cares for a patch of irises that bloom in magnificent glory for hardly two weeks. The amaryllis plant sits in somnolence in its pot in the basement all winter, then suddenly awakens in March and puts forth two unimaginably beautiful blossoms. In just ten days the flowers fade and the show is over for another year. This is reality; this is the fact of life and the fact of death that is so hard to accept.

Shepherds spend night and day in early spring playing midwife to ewes, sometimes working desperately through the night to save lambs from dying at birth. Kneeling in manure and afterbirth with your arm up to its elbow inside a ewe is hardly fun. Then all summer the ewes and lambs must be watched and wormed and protected from maggots and wolves and coyotes and the neighbors’ damned dogs. Why do we do it? It’s certainly not for money, because most of us don’t make much as shepherds. But when those lambs go bouncing across the green spring pasture, all the pain and suffering that got them there is forgotten and the shepherd rejoices. Then comes autumn, and those lambs upon which one has spent so much labor and love are shipped off to the stockyards and to death. A friend, a farmer all his life, tells me a story that brings tears to his eyes. Once, after he had hauled his steers off to the stockyards, he stayed to watch them sell. The large building in which the animals from each farmer were penned separately until they were auctioned off had a catwalk above it from which the animals could all be viewed. My friend went up there to look at his charges one last time, and as he talked with another farmer, his steers recognized his voice, lifted their heads, and bawled at him piteously.” They heard me. They were crying out for me to save them,” my friend says. “It just shook my soul.”

I used to ask myself what kind of perversity drives us gardeners and farmers to settle for such a life, but it was only when I faced death from cancer that I could start to answer that question with any conviction. Carol had to do most of the gardening that spring because I was so weak. But sometimes between chemotherapy sessions, I had energy enough to sit in a chair and, seated, weed by hand and with hoe. Actually, pulling weeds or hoeing from a sitting position is not comfortable, so what I really did most of the time was get down on my hands and knees, pull a few weeds, use the chair to pull myself up, sit awhile to catch my breath, stand up and hoe a bit, and sit down and rest some more. Working this way forced me into a very close relationship with the life around me. One of the first tasks that I set out to accomplish was to clean up the black raspberry patch, which had been neglected for a year. Instead of roaring down between rows with the tiller or hacking vigorously along with the hoe, always in a hurry, I was sort of enclosed within the raspberry vines, which had spread out from the original rows and seemed more like a little jungle than a garden. I could only weed or hoe or prune the vines closest to the chair, then pick up the chair and advance a little farther along. I had to step on some of the vines, or push them out of the way or get entwined within them. I was, in other words, in close communion with raspberrydom.

Being that close to the plants for long periods of time, I became very aware of a whole kaleidoscope of natural life around me, much of which I had never really focused on before. I expected to find the perverse chickweed, the cursed sow thistle, and the stubborn dandelion, but where on earth did that lovely dill plant come from? Could I just leave it to grow there? (Yes—when you are weak, companion planting of just about anything suddenly works fine.) And what was this strange grass that was spreading so rapidly over the ground? It looked a little like bluegrass until it went to seed, which it did in what seemed like three hours. In fact I counted nineteen different kinds of weeds under the raspberry plants. This was in an area of about fifteen feet wide by thirty feet long. One of them was bedstraw. Where on earth had that come from?

Tree seedlings were gaining a firm toehold, too, much to my dismay. A raspberry patch, at least the way I manage one with leaf mulch, becomes a tree nursery heaven, especially when located next to a tree grove. In just one year of not weeding, there were at least a score of white ash seedlings and a dozen black walnut seedlings that had popped up under the berry vines. That’s how I learned that the fervor for planting trees à la Arbor Day rituals is mostly unnecessary. If there are trees anywhere in the vicinity, just lay down a foot of leaf mulch where you want more to grow and stand back. The trees will come, believe me. There were several two-year-old ash seedlings among the raspberry canes that, because I had not had the opportunity to sit still among the vines, I had missed the previous year. They were five feet tall already and growing above the berry vines! A transplanted seedling will never grow that fast.

These seedlings were telling me something else. Just because all the old white ash trees were dying out from emerald ash borer depredation, it did not mean the end of the white ash. Seedlings were growing all over the place, and they will continue to grow, like elm seedlings had done, to seed-bearing age before the emerald ash borer can wipe them out. The ash borer, like the elm beetle, will run out of big trees to feed on and be so drastically reduced in numbers that the young trees will start producing seed for more trees before the borer can kill them.

That’s when the thought hit me. In nature, nothing much really dies. The various life-forms renew themselves. Renewal, not death, is the proper word for the progression of life in nature. If I died of cancer, the proper response would be to bury my flesh and bones for fertilizer in a celebration of natural renewal.

This excerpt is adapted from Gene Logsdon’s Gene Everlasting (January 2014) and is printed with permission from Chelsea Green Publishing.