The Farm Bill

The current federal Farm Bill expires in September. The U.S. Senate and House need to craft a vision of what our food system should look like before that time, one that garners enough support to pass. Make no mistake: This massive piece of legislation has a very real impact on what is on our plates, the quality of our drinking water, the preservation of rural landscapes, the vitality of our communities, public health and more.

The process starts when the House and Senate develop their separate bills. As each chamber of Congress has passed their own version, a conference committee was appointed to resolve the differences. Once that is done, the final bill goes back to each chamber for a vote and then is forwarded to the President to be signed (or vetoed).

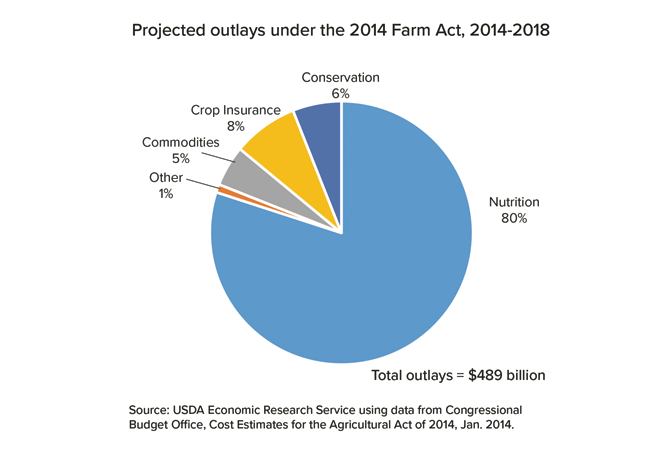

The bill’s 12 sections, called titles, address, among other things, rural development, conservation, crop insurance and “specialty crops” (fruits and vegetables). The largest and most contentious part of this legislation is the nutrition title.

The House version of the bill includes work requirements and changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which may increase food insecurity for more than one million low-income households. Reduced SNAP benefits would also have negative financial repercussions for local grocers and farmers markets. According to the Farmers Market Coalition, SNAP participants spend more than $19.4 million each year at farmers markets. A reduction in this spending would be felt by many small farmers and businesses across the country. These changes resulted in strong partisan divisions in the House when voted upon earlier this year.

The House Farm Bill: A Rotten Tomato

Aside from provisions that would cause hardship to those most in need of food assistance, the House Farm Bill also fails to provide mandatory funding for programs like the Farmers Market and Local Foods Promotion Program, which invest in farmers markets and local and regional food systems. Sales of direct-marketed foods have increased, more people attend farmers markets and farmers and local food businesses have had more opportunities as a result. The House bill also fails to invest in farmers interested in developing shelf-stable and valueadded products to increase their economic viability. It eliminates funding for certified organic farmers to offset the costs of annual certification.

This bill does not adequately fund the Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program (BFRDP) at a time when 100 million acres of farmland will change hands and the average age of farmers is close to 60. Nearly 40% of Ohio farmland is rented or leased from someone else and 87% of that land is owned by non-farmers with an average age of 68. Interest in farming as a career is booming among young people starting out and others starting a second career. The need for programming to help beginning farmers access information, technical assistance, land and credit has never been greater.

The House bill cuts conservation by $1 billion and funding for working lands conservation programs specifically by nearly $5 billion over 10 years. The toxic algae blooms choking Ohio waterways dramatize that how we grow our food impacts our environment. Investing in conservation helps farmers grow food in a way that contributes to water quality, decreases soil erosion and improves pollinator and wildlife habitat.

Overall, the House bill helps the big get bigger and the rich get richer. Federal policy has historically contributed to farm consolidation, and the homogeneity and inequity caused by consolidation, by directing disproportionate resources toward the largest and wealthiest agribusiness operations. The House bill exacerbates this trend by getting rid of a 30-year-old rule that prevents corporations from receiving unlimited commodity payments (the price and income support payments that go to growers of commodity crops like corn, wheat, rice and cotton).

After this flawed bill failed to pass the first time, a second try yielded a two-vote margin of victory, split along party lines.

The Senate Farm Bill: A Cherry Tomato Mix

In striking contrast, the Senate version of the Farm Bill was developed in bipartisan fashion. It scales up investments in local and regional foods through the Local Agriculture Market Program championed by Senator Sherrod Brown. This provision provides permanent mandatory funding for local food initiatives such as the 2015 project by Great River Organics that helped coordinate production aggregation and distribution of local certified organic produce.

As Senator Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) said during the committee debate on this bill, it “builds the bench for the next generation” of farmers and ranchers by providing permanent, mandatory funding for BFRDP. This forward-looking investment is a major difference with the House bill, as is an important amendment to the “actively engaged” in farming rule that would prevent the wealthiest farmers from receiving unlimited subsidies. The Senate bill maintains level funding for conservation programs overall although it does reduce funding for two of the programs that support working lands conservation. In reviewing both bills, we must ask, “show me the money.” Ultimately, many of the provisions in a bill don’t move forward unless they have mandatory funding. A program may be “authorized,” but unless funding is appropriated every year, it will be a program in name only.

Given these drastically different visions for the future of food and farming and the inclusion of mandatory funding for key sustainable agriculture and local food initiatives, we look forward to seeing how the conference committee crafts a compromise that will be acceptable to both chambers of Congress. They have until the end of September to get it done. Let’s hope they embrace the Senate’s more constructive vision for the future.