Pickin’ up pawpaws, put ’em in your recipe

If you love pawpaws—as more and more people do—you probably have discovered the pleasure of enjoying Ohio’s native tropical fruit in its simplest form: fresh, raw and immediately after you’ve foraged one from the woods or trail.

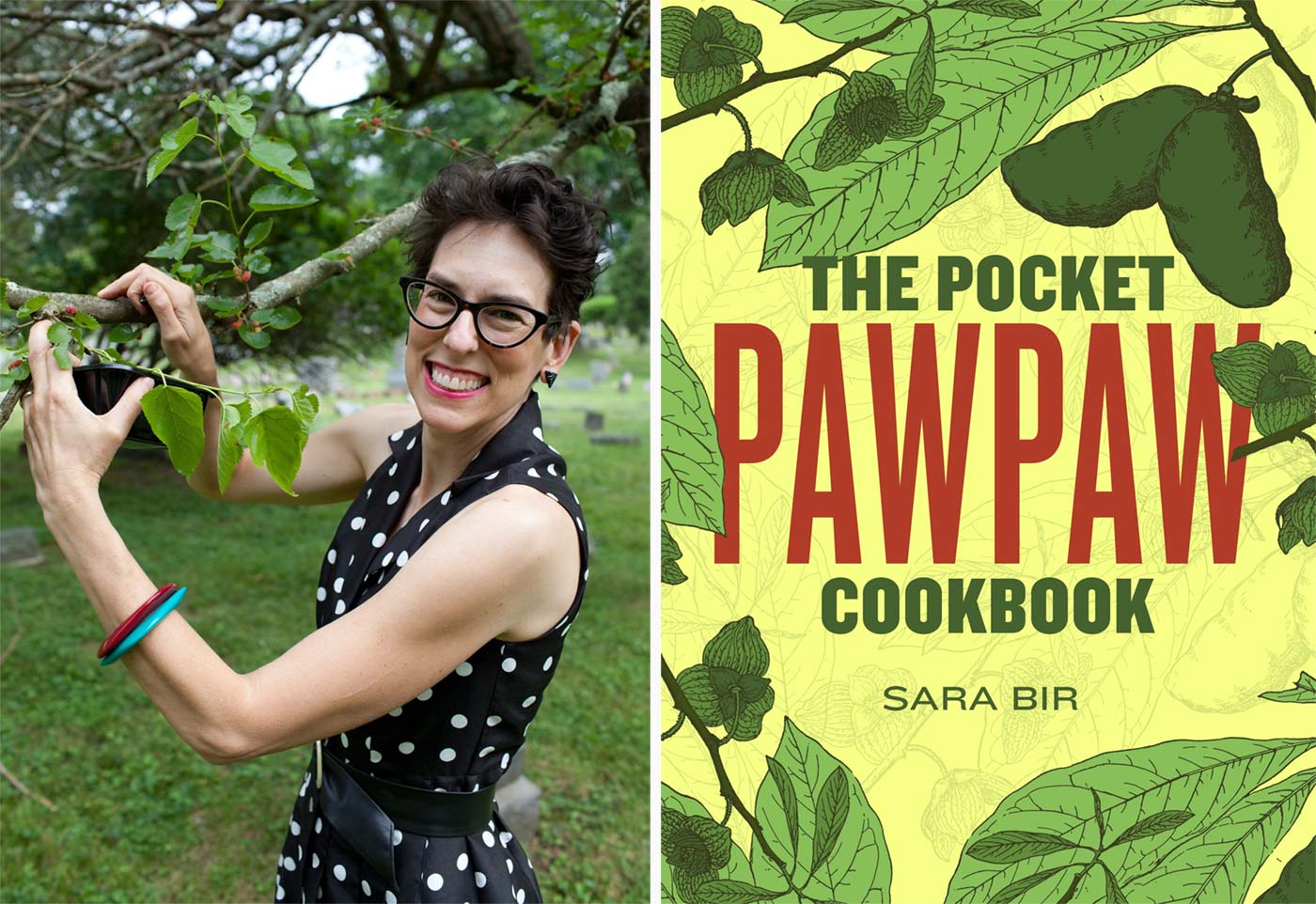

Chef and cookbook author Sara Bir even begins the newly released second edition of her The Pocket Pawpaw Cookbook with a passionate argument in favor of eating pawpaws in just this way.

“Work the flesh out of the skin. Raise it to your lips and slurp. It will be sweet and creamy and totally new—every pawpaw in the woods is like your fist pawpaw all over again,” Bir says.

So, as even Bir asks, if pawpaws are so good plain, why cook with them?

For many, including her, the urge to play with a new and exotic ingredient is hard to resist. What other flavors and textures would go well with this? What new dish can highlight the pawpaw’s charms?

But also, cooking pawpaws into recipes is one way to make the fruit last beyond its brief late-summer-to-early-fall season. The scarcity and seasonal limitations of pawpaws are part of what make them so magical.

We’ve gotten used to being able to shop for most other kinds of fruit all year round, and we’ve lost sight of the notion that they even have seasons. Pawpaws do not allow us this luxury.

“We can go to the grocery store and order things online and have whatever we want wherever we are,” Bir says. “That’s an artificial construct.”

Like many pawpaw fans, Bir was enchanted from the first time she encountered a pawpaw on a trail near her home in Marietta. An Ohio native, Bir traveled and then moved back to Ohio in 2014. She had heard of pawpaws but never seen one. Then one day on a hike she spotted something weird on the trail.

“I saw this squished thing,” she said. “It smelled like a fruit and it tasted like a fruit. I figured this must be a pawpaw. It was a little like seeing Bigfoot.”

CAUTION IN THE KITCHEN

Like most of us, though, she had a hard time finding any recipes for pawpaws. “I decided the world really needed a resource for pawpaw recipes that make sense for that fruit.”

Developing recipes for pawpaws, though, is tricky. Along with having a fairly brief season, pawpaws generally must be foraged from pawpaw trees in wooded areas. They have a short shelf life and don’t travel well. And those are just the challenges for acquiring them.

Ohio University Professor Robert Brannan is a food scientist, pawpaw expert and president of the National Pawpaw Foundation. “The biggest thing with pawpaw is you start with this liquidy pulp,” Brannan says.

Unlike other fruits, cooking it down to reduce pawpaw is not a good idea. The fruit has a compound that, when concentrated, induces vomiting.

Scientists believe the compound is part of the pawpaw tree’s defense against predators. But the compound also collects in the fruit. Consuming small quantities usually doesn’t cause a problem. But eating large amounts of pawpaw, or eating dishes that contain concentrated amounts of pawpaw pulp, can bring on unpleasant, nauseating consequences.

“It’s a drawback,” Brannan says.

It’s one Bir encountered firsthand in developing recipes for her book. Using a tried-and-true banana granola recipe, Bir mashed pawpaws with granola and baked the combination for a long period at a low heat, only to discover that the process had concentrated the nausea-prompting compound. “There was a lot of trial and error,” she says. “And there are a finite amount of recipes for something like this.”

Bir left the granola recipe behind, but she went on to develop key lime pawpaw pie, pawpaw salsa, pawpaw banana ketchup and more for her book.

Pawpaws pair better with some things than with others, Bir discovered. They taste good with honey and they go well with dairy, particularly fermented dairy like yogurt, she says. “The way it behaves, the way it ripens, a pawpaw is very much its own thing.”

A FORAGER'S TREASURE

Some good news about working with pawpaws is that they’re nutritious. Much like the fruits they most taste like—bananas and mangoes—pawpaws are a good source of antioxidants and fiber. The skin, which many North Americans discard, is not only also edible but just as nutritious as the pulp.

Also, the pulp does not lose its flavor or texture when it is frozen, though it may turn brown through oxidation, like avocadoes or apples. Many cooks work with frozen pawpaw pulp because freezing is a reliable way to preserve the fruit during the relatively brief season.

Though some people cultivate pawpaw trees, many cooks, including Bir, forage their fruit. And that foraging starts with scouting some of her favorite pawpaw trees early in the summer, looking to see which have blossoms and developing fruit. “I love spending time outside and that’s a really great pursuit,” she says.

In 2015 she self-published the first edition of The Pocket Pawpaw Cookbook. “When I sold out of that first edition I had some new recipes,”

So she worked with Belt Publishing to produce a second edition, which was released in August, just in time for pawpaw season. As the pawpaw trees begin dropping their green potato-shaped delicacies, you will find Bir among the other pawpaw enthusiasts, out foraging for enough fruit to freeze and experiment with for another year.

Pawpaws force us to respect their timetable, to enjoy them when and where we can find them.

“They’re elusive,” Bir says.