A Tale of Two Cooks

It is the best of times, it is the worst of times, it is the holiday season. To be fully together with friends and family after a year that kept us apart is a beautiful thing—but the idea of cooking again for a large gathering can be stressful too, depending on the type of cook you consider yourself.

The first type is the non-recipe-follower, the person who cooks perfectly well without ever glancing at one. Large gatherings? No problem. Complicated holiday meals? No sweat. There’s one in every family—my brother is such—and these people tend to be equally lovable and maybe even slightly annoying to the recipe followers.

The second type of cook is one who must follow a recipe to a T, otherwise disaster will ensue. With a heavy sigh (and a bit of sibling begrudgery), this is where I must admit that I belong.

I know I’m not alone in lacking that certain je ne sais quoi in the kitchen, which left me considering the role of recipes when it comes to cooking for a full table of guests, particularly the holiday gatherings. I wondered, what actually makes a good recipe? Are there helpful tips for following one? Most of all, will one sibling be doomed to follow recipes forever, while the other one forever gets the culinary glory?

As we ponder these questions, let’s first look at what constitutes a good recipe.

THE ANATOMY OF A GOOD RECIPE

Today, a reader would be hard-pressed to find a recipe book that didn’t include the basics, but this wasn’t always so.

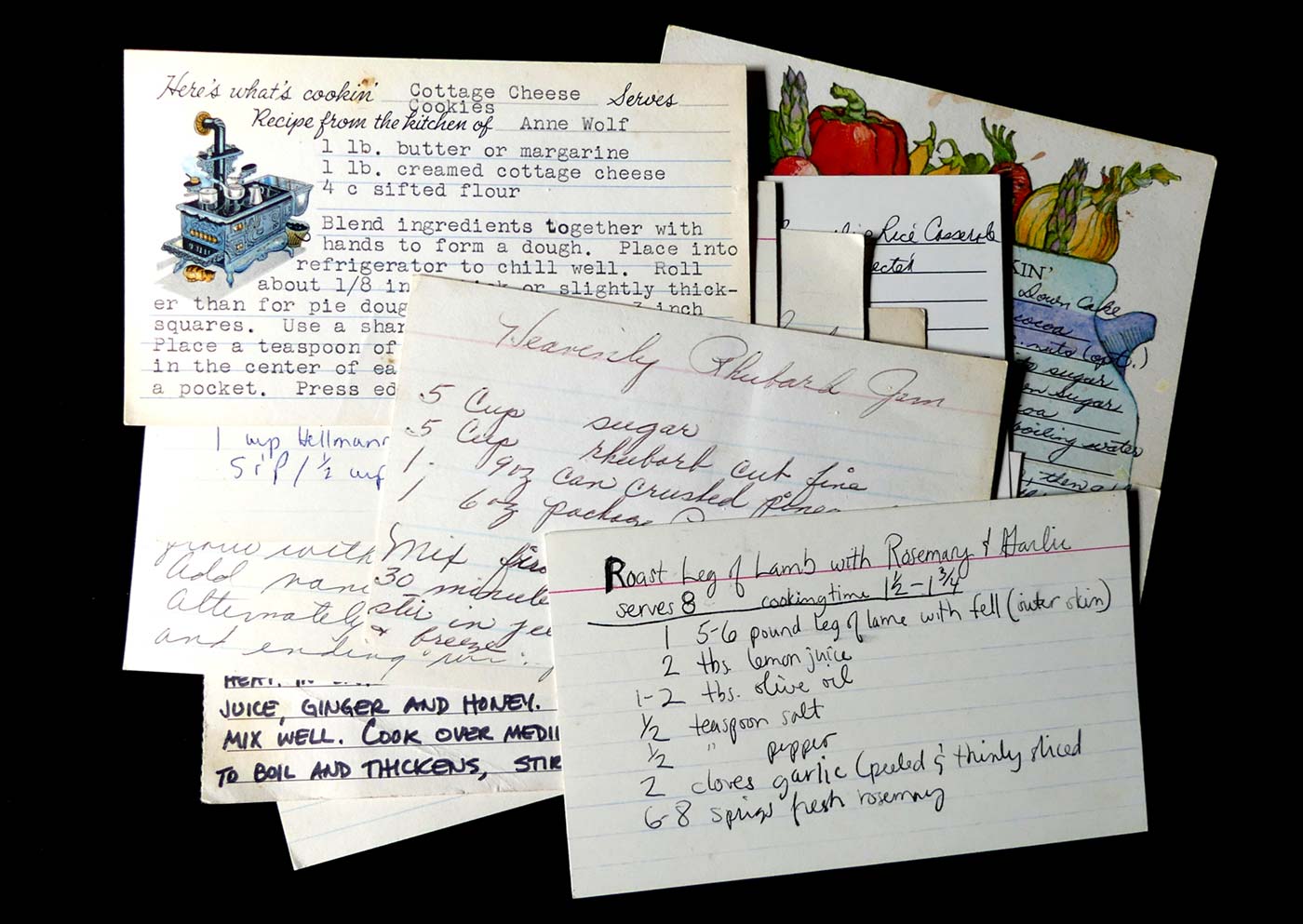

By about 1650, it had become common for households to keep “receipt books” of recipes to pass on to their eldest daughters. Vague at best, confusing at worst, these books left much to be desired. Take, for example, this English recipe for herring pie published in 1669:

“Put great store of sliced onions, with Currants and Raisins of the sun both above and under the Herrings, and store of butter, and so bake.”

Hopefully, the reader knew how much a “great store” quantified, how to properly make a pie crust and had the knowledge that English pies have crust on the top and bottom, as well as how long to bake the pie and at what temperature.

Fast forward to the 1800s, and many cooks were fed up with the vagueness. In 1816, Dr. William Kitchner started giving precise measurements for every ingredient in The Cook’s Oracle. Later, Isabella Beeton introduced even more radical ideas in Household Management, including cooking times, number of servings and preparation time, and it was Fannie Merritt Farmer who insisted measurements should be standardized in The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book.

Today, a good recipe goes even further. Many include ingredients in multiple weight formats, context clues for timing (such as descriptors for how a sauce should look) and explanations for why particular steps are important (and therefore should not be skipped)—all of this in an effort to say farewell to uncertainty.

HOW TO FOLLOW A RECIPE

The very first time I made boeuf bourguignon, the savory stew didn’t cross anyone’s lips until 11pm. This is because I briefly laid eyes on the recipe to see if I had the ingredients and then threw caution to the wind—thus a three-hour recipe turned into six. This perhaps explains why I’m in the second category of cooks, but thankfully, chef Tamar Adler has specific tips for following recipes.

First, she recommends reading the entire recipe, start to finish, several times.

Next, consider when to prep your ingredients. If cooking occurs in quick succession, chop and prepare everything before you start. If timing is flexible, there’s no reason you can’t chop as you go.

Third, understand the purpose of each ingredient. For example, if an herb is added at the beginning, it plays a role in the meal’s essence, whereas adding it at the end makes it a garnish.

And finally, use common sense. If a recipe calls for a cup of chicken and a cup of salt, perhaps it’s best to seek counsel elsewhere.

THE ROLE OF RECIPES IN THE HOLIDAY SEASON

While it may be tempting to use the holidays as a chance to try a new recipe, it’s best to resist the urge and instead cook what you know. When you cook new recipes at a large gathering, you risk spending time scrambling through instructions instead of enjoying time with your guests. Familiarity also helps to build cooking confidence over time—a beautiful irony in which the more you use a recipe, the less you’ll need it.

Let’s also consider the possibility that, like my brother, you’re a natural-born cook. To oppose the use of recipes might be to find them constraining, unimaginative, formulaic. But according to food writer MFK Fisher, that’s precisely the point.

“A recipe is supposed to be a formula, a means prescribed for producing a desired result, whether that be an atomic weapon, a well-trained Pekingese, or an omelet,” she wrote. Weapons and wooly dogs aside, a formula is exactly what’s necessary for ensuring food gets on the table during the holiday season. Even the most skilled home cook can benefit from the structure of a recipe when 20 guests are due to arrive in only a few hours.

So whether you’re the natural cook of the family or not, recipes undoubtedly help the holidays go smoother. As one recipe fan to another, may I suggest pulling out your Dutch oven for boeuf bourguignon if you want to skip the turkey this year? Just make sure to (actually) read the recipe and (definitely) practice it a few times before the big day. This year, the culinary glory just might be yours.