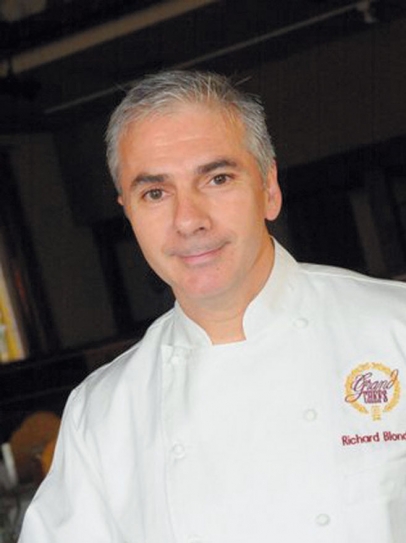

At the Top of His Game: Chef Richard Blondin of The Refectory Restaurant and Bistro

When Kamal Boulos, ebullient owner of The Refectory, describes the talents of his executive chef of 24 years, Chef Richard Blondin, the superlatives roll.

“Richard is an extraordinary culinary athlete with a commitment to excellence. That was my vision for The Refectory—to have the best chef I could find.” Kamal clearly feels he has found that chef. “Richard pushes himself to do new things. Every few weeks he does something I’ve never seen.”

The chef himself, neat and trim at age 54, says only: “We stay busy, so I’m assuming it’s okay for our clients.”

Not from this modest chef will you learn that he was a finalist for the James Beard Award in 2012, or that The Refectory ranks first in Columbus fine dining in the hearts of both food critics and diners. No, he keeps the challenge of producing superb French cuisine for 160 diners per night (and up to 400 on holidays) ever before him.

“Volume is like a wall with fine dining,” Chef Richard says, explaining that with fewer diners, a chef can cook at a higher level of sophistication and vice versa. When he first came to the United States in 1989, he cooked at the much-admired but now defunct L’Auberge, which seated only 80. There he learned English and met his American wife, Jackie.

When Chef Richard came to the much larger Refectory in 1992, Kamal encouraged him to completely revamp the kitchen in order to do the kind of cooking he would become known for.

Becoming a Chef

Chef Richard grew up near Lyon, France, where his father raised vegetables, fruit like pears and raspberries, and even rabbits. “The grocery store was for bread and starches,” he says. “Otherwise, we grew it.”

His father cooked, his grandmother cooked, and his oldest brother, Bernard, was a chef. These influences “made me who I am now,” says Chef Richard. “When I was 14 or 15, I liked to make a few dishes—a little vinaigrette there, a sauce here.”

Chef Richard followed the traditional French path into the world of fine dining, attending culinary school and working for a year or two at a number of Michelin-starred fine dining establishments in Lyon, even flirting briefly with becoming a pastry chef until sidelined by a gluten allergy.

Under his direction as executive chef at Le Bellecour in Paris, the 39-seat restaurant within walking distance of the Eiffel Tower recovered the Michelin star it had lost just before his hiring.

Learning From the Best

At age 18, Chef Richard worked under his first great chef. “From Pierre Orsi, I learned about the idea of sophisticated food,” he says. “I did really get from him organization and how to work very clean. The kitchen was disciplined—no talking. At the end of the night, he left and his wife, the maître d’, checked every station in the kitchen. None of us could leave until maybe 1am. But when we came back the next morning, it was like a brand new kitchen. This is definitely still in my mind.”

After two years at Pierre’s two-star restaurant, Chef Richard was ready to work under Paul Bocuse, one of the pioneers of nouvelle cuisine and the founder of the Bocuse D’Or, an internationally renowned cooking competition. With a single phone call, Pierre secured a place for Chef Richard.

“It is like the Mafia in France,” he says. “All the chefs know each other.”

At Paul’s three-star restaurant, “we learned how to work at a fast pace. There were many different techniques and presentations that were out of this world.”

Chef Richard recalls roasting pheasant and duck on a rotisserie in the restaurant dining room in front of the guests. “I had to go back and forth from the kitchen, raising the meat higher as it cooked, then replacing the cooked bird. It was very technical and difficult. They cook there like they used to do back in the French court. And everything was fresh—no freezer, and no canned food in the kitchen.”

He adds, “It was like the military. You always had to say, ‘Yes, Chef!’ even if you were being scolded.”

The Philosophy of a Chef

Chef Richard’s food is first of all, French, but “not too much extreme French with roux and heavy cream.” He describes his cooking style as nouvelle French classic, but more contemporary in presentation.

“I like simplicity on the plate. Complicated doesn’t mean better. And I like what makes sense on the plate, what is seasonal.”

He emphasizes fresh ingredients. “I buy locally as much as I can. It is a much better product, and I can see it before I buy.” He laments that in the United States, some specialty items, such as veal sweetbreads and game meats, are only sold frozen.

“I regard cooking as an art,” he says. “On the same plate, I want contrast of texture, color, and technique. Something crunchy, something soft. Something cold, something warm. I make sure there is as much color as possible.”

He pauses to shake his head. “Every contrast except sweet and salty. Some chefs do it, and it is okay, but—truffles and foie gras together in a dessert?

Mango with venison? That’s just not me, I can’t do it.”

Predictably, Chef Richard is his own most severe critic.

“I always question myself. I am 100% positive it could be better,” he says.

His satisfied diners would disagree, but no doubt it is Chef Richard’s drive for perfection that produces the food they love.

Enjoy Chef Richard’s cooking at The Refectory Restaurant and Bistro, 1092 Bethel Road Columbus, Ohio 43220; 614- 451-9774; reservations recommended.

Game On

Chef Richard Blondin of The Refectory offers his thoughts on cooking wild game

A highly regarded game chef, Richard Blondin showcased his best recipes in his cookbook, The Hunter’s Table, at the suggestion of The Grumpy Gourmet, Doral Chenoweth, former food critic for the Columbus Dispatch. Now sadly out of print, the book is still available used through Amazon.com. We feature one recipe here (see page 54), along with Richard’s game-cooking wisdom.

Frenchman that he is, Chef Richard admits to being partial to the use of game in terrines and pâtés, and game features prominently in his fall and winter menus at The Refectory.

“Last winter we did a tableside game dinner with venison, elk, and wild boar. It was very, very popular—I couldn’t get enough meat to keep up with the demand.”

Chef Richard explains that game served in American restaurants must be farmed, butchered, and USDA-inspected rather than shot wild. One meat specialist, D’Artagnon, meets this requirement by freezing wild-shot Scottish game birds like grouse and shipping them to the United States for inspection. When these birds appear on the table, Chef Richard says, “The servers always warn you to look out for buckshot.”

Of course, the home cook who hunts or knows a hunter can dress his own wild game or have it locally processed by experts such as Thurn’s Specialty Meats in Columbus.

In Europe, according to Chef Richard, true wild game is common in restaurants. “It has a very strong flavor. Either you like it or you don’t.” The meat often looks different: “Wild pheasant meat is purple versus farm-raised, which is slightly darker than chicken dark meat.”

Chef Richard emphasizes that game meat is very lean and must be handled accordingly. Game can be substituted in recipes that use similar cuts (e.g., venison loin for beef loin) with these caveats for the home cook:

• Marinate the meat in fat or oil, NOT in an acid like wine or vinegar. Save the wine for a reduction sauce later. If you marinate in a Ziploc bag, you can use your hands to massage the meat from the outside.

• Cooking times will be shorter. Overcooked game becomes tough and dry—this is true of any meat, but overcooking happens more quickly with game.

• Use seasonal ingredients: juniper berries, sage, cranberries.

You can find a selection of game locally at North Market Poultry and Game (59 Spruce Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215, 614-463-9664) or order online from D’Artagnan.com. Weiland’s also has rabbit (locally-raised) year-round. They also carry pheasant in November for Thanksgiving along with duck (breasts and whole ducks, plus duck bacon). For local hunters, Thurn’s (530 Greenlawn Avenue, Columbus, Ohio, 43223, 614-443-1499) will process wild game that is field dressed prior to drop-off.