The Way of Water: Central Ohio’s Watersheds and Our Food System

At the end of my street the Olentangy River rushes by, a refuge in my relatively urban Clintonville neighborhood. The sound of the water moving through the river’s banks is therapy, relished by onlookers on park benches, exercise enthusiasts on the Olentangy Trail and kayakers in the river.

Gazing at the river, I am reminded how precious it is in the web of interconnected waterways in our city, our region, our state and beyond. The river faces constant threat from myself and my neighbors, yet it never ceases to provide and inspire.

What Is A Watershed?

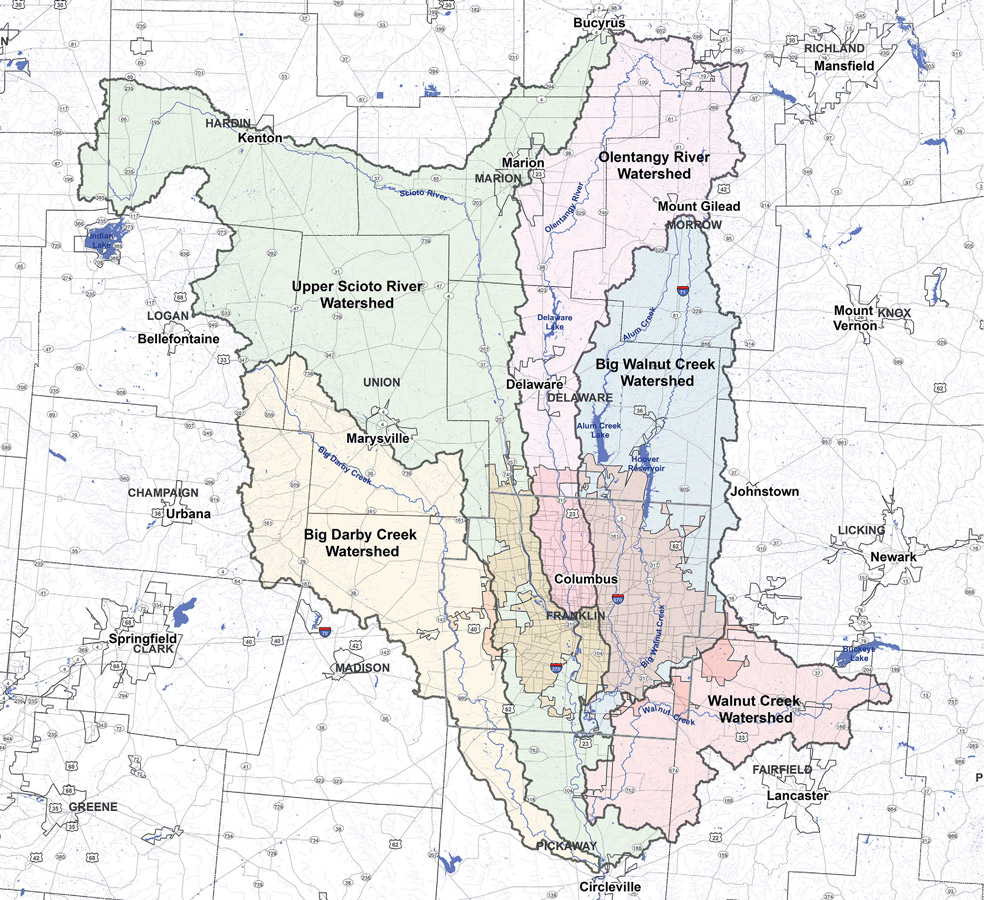

A watershed is defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as “land area that drains to a common waterway, such as a stream, lake, estuary, wetland, aquafer or ocean.” Watersheds come in a variety of sizes, irrespective of municipal, state or international borders. The dynamic interaction among humans, water and the land directly impacts the quality of waterways and the cost to treat water to ensure safe consumption.

In Central Ohio, the waterways in our region reside in the Scioto River watershed, which provides drinking water for more than 2 million people in the Columbus metro area alone. The watershed stretches through 31 counties in Central and Southern Ohio, incorporating more than 6,500 square miles. The northern part is dominated by rural land, while cities like Columbus and its suburbs, Chillicothe, Circleville and Portsmouth, dot the watershed. The Big Darby Creek, Walnut Creek, the Scioto and Olentangy rivers, amongst other bodies of water, are situated in the watershed.

“In Franklin and Delaware counties, the biggest threat to our water quality is development, including impervious surfaces such as parking lots, rooftops and roads,” explains Ryan Pilewski, Watershed Resource Specialist at the Franklin Soil and Water Conservation District.

“Development continues to degrade our Central Ohio waterways due to a lack of stormwater controls that protect stream banks from erosion. Rural waterways are facing threats from agriculture and home sewage treatment systems,” Ryan notes.

It All Begins in Your Backyard

Our region has faced rapid growth in recent decades and, according to the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission (MORPC), from 2010 to 2015 Central Ohio added 115,000 people.

MORPC estimates that by 2050 the region will add upward of 1 million people, making Central Ohio the most populous area in the state with more than 3 million residents. This influx puts strain on the water resources in our region, in particular in the form of new development that lacks ecological management of stormwater runoff.

“In Central Ohio, we have the problem of people not valuing stormwater. We try to rush it away from our properties as soon as possible. It’s a precious commodity that we could be taking better care of,” says Laura Fay, the Science Committee Chair for Friends of the Lower Olentangy Watershed (FLOW), a local nonprofit. “With development being the biggest threat to our watershed, we would like to see compliance or adherence to the concepts of balanced growth.”

“We want to slow down stormwater,” Ryan adds. “It is being rushed through pipes causing erosion in our rivers. We want to slow it down in the uplands. That could be by protecting existing wetlands or mimicking wetlands by infiltrating water into the ground using rain gardens or storing it in cisterns or rain barrels.”

Residents play a vital role in both threatening and protecting our region’s watershed. Backyard conservation efforts are crucial to the health of our waterways. Through the Franklin Soil and Water Conversation District’s Community Backyards Rebate Program, partnering communities work with the district to offer Franklin County residents a rebate for the purchase of rain barrels, compost bins and native plants or trees, in exchange for online or in-person education on stormwater runoff reduction practices.

“We use rain barrels as a gateway to get people interested in the topic—it’s a little carrot out front,” explains Kurt Keljo, Watershed Resource Specialist at the Franklin Soil and Water Conservation District.

“We encourage people to use a rain barrel to water their garden but in our workshops, we talk about how a rain barrel is just a first step and we introduce them to other conservation practices that can help infiltrate stormwater into the ground,” Kurt says.

Cisterns are also encouraged. As are rain gardens, native plantings, drip irrigation systems and responsible lawn care maintenance. Additionally, the installation of permeable surfaces, green roofs and composting systems are tactics taught by conservation program educators.

Trees Play a Crucial Role

“Trees make a big difference and planting them is a very good thing,” Kurt emphasizes. “Trees do a lot to reduce runoff by intercepting, infiltrating and transpiring rainfall.”

Through its Branch Out Columbus program, the City of Columbus aims to plant 300,000 trees by 2020 in an effort to replenish the city’s tree canopy. In addition to helping to mitigate the heat island effect, which occurs when a metropolitan area’s air temperature is warmer than in surrounding rural settings, trees help to control stormwater runoff by capturing rainfall in the tree canopy and the deep root system of trees assists in water infiltration.

Choosing to plant native varieties of plants and trees is important. In addition to supporting native birds and insects, “native plants have larger root systems, which helps to break up the soil and enables water to infiltrate deeper,” Ryan explains.

How Is This Related to Our Food?

Agricultural runoff occurs when water from rain, snow or a farm irrigation event lacks absorption into the soil and travels to nearby waterways carrying with it excess nutrients, such as dissolved phosphorus and nitrogen, or animal manure from a farm. This type of pollution is a serious issue impacting our waterways, as was shown in the 2015 and 2016 nitrate advisories for a number of Franklin County neighborhoods due to farm runoff into the city’s drinking supply.

On its website, the City of Columbus notes: “The Scioto River receives runoff from more than 1,000 square miles of land, 80 percent of which is agricultural, before reaching the Dublin Road Water Plant intake. Therefore, the Scioto River is more susceptible to nitrogen runoff than the other water sources in Columbus.”

Additionally, our region’s watersheds feed into the Mississippi River and the health of our ecosystems greatly impact those downstream from us. Agricultural runoff from our area has contributed to the growth of an algal bloom the size of Connecticut in the Gulf of Mexico, making it impossible for fish and other aquatic life to survive in the affected zone.

Supporting growers who farm sustainably is key. Shopping local also has an impact as vehicle exhaust contributes to stormwater runoff and the less food has to travel the better it is for the environment.

“Encouraging local producers to use responsible practices is important,” Kurt says. “I don’t think that local agriculture is the enemy of streams—it all depends on how farming is done. The Big Darby is in great shape despite being surrounded by agriculture for many years. As agriculture has become more intensive, the impact on water quality and stream health has increased.”

“It’s the same with development,” Kurt continues. “We know how to do both of these in a way that’s less likely to impair streams. We are not facing a science problem as we know what to do to make responsible ecological decisions. It’s actually a social problem. It’s a question of whether or not we are willing to do the things that we know that we need to do to keep our waterways safe.”

Combining food and good water management practices, FLOW has worked with partners around the region, including The Crest Gastropub and Stratford Ecological Center, to install edible rain gardens. Rain gardens feature shallow depressions that enable runoff to gather and infiltrate into the soil. Rain gardens are generally composed of native plantings due to their deeper root structure. An edible rain garden can be planted with any kind of plant or herb.

FLOW has also partnered with the Anheuser- Busch plant in Columbus to improve the ecological footprint on the company’s land. Laura notes that initially FLOW was surprised that a brewery would approach them with a partnership opportunity. However, since water is a major resource used in beer production and, due to this, Anheuser-Busch is the second largest user of water in the area, this partnership in fact makes a lot of sense.

FLOW recently worked with Anheuser- Busch to plant trees on the company’s property with the goal of intercepting excess runoff into Rush Run, a nearby creek. The two organizations have since developed a five-year plan to plant prairies, trees and a rain garden on the brewery’s lands.

Get Involved

A number of organizations in our area are working to preserve Central Ohio’s watersheds. These groups welcome volunteers for service events such as waterway clean-ups or tree plantings. Many also offer educational programs for the public, including training and support for backyard conservation practices such as the installation of rain barrels or cisterns, rain gardens and permeable surfaces, as well as education on responsible lawn care maintenance, amongst other topics.

Some of the organizations working to protect our waterways include:

Franklin Soil and Water Conservation District

Friends of the Lower Olentangy Watershed

Friends of Alum Creek and Tributaries

To learn more about watershed groups across the state of Ohio, visit the Ohio Watershed Network.