HOPE FOR HEMP IN THE MIDWEST

Graphics by Caryn Scheving

How changing legislation is offering a second chance for America’s most misunderstood plant

In 2018, Mark Boyer, a sixth-generation farmer and owner of Boyer Farms in Indiana’s Miami County, was the first non-university grower in decades to legally plant industrial hemp in a traditional agricultural row-crop setting in the state’s soil.

“It was a successful project,” Boyer says during a break in planning for his 2019 growing season. “I was determined to use only traditional farm equipment, what was already in my shed, to grow the crop. I learned a few things. Some of the things you hear about hemp are true and some are myths.”

Boyer farms 1,250 acres, most of which he devotes to traditional commodity crops: corn, soybeans and wheat. On 350 of these acres Boyer cultivates sunflowers and canola and uses his on-farm cold press to expel oil from the crops’ seeds. The oil supplies Healthy Hoosier Oil, Boyer’s line of specialty cooking oils that are distributed across the Midwest.

In 2018, through a partnership with Purdue University, Boyer grew industrial hemp on 12 acres, also pressing these plant’s seeds for oil—this time in the name of research. Under Indiana law, Boyer was not authorized to sell his hemp seed oil for profit and when we spoke recently the final product was in a lab to determine shelf life, sell-by date and nutritional profile.

A COMPLICATED HISTORY

Industrial hemp is believed to be one of the first plants spun into fiber thousands of years ago. An adaptable plant that grows in many climates, a Popular Mechanics article from the 1930s noted that, even then, hemp had over 25,000 known uses. The stalk offers fiber, which is coveted by the textile and construction industries and can be used for a range of other uses such as animal bedding. The seed, which can be eaten, is an excellent source of protein, fiber and healthful fatty acids. As Boyer has researched for Purdue, the seed can also be pressed for oil for use in cooking and cosmetics. CBD, or cannabidiol, can be extracted from the plant and is of great interest to the natural pharmaceutical industry. Proponents claim that CBD can naturally soothe a host of ailments from anxiety to insomnia, all without intoxicating the user.

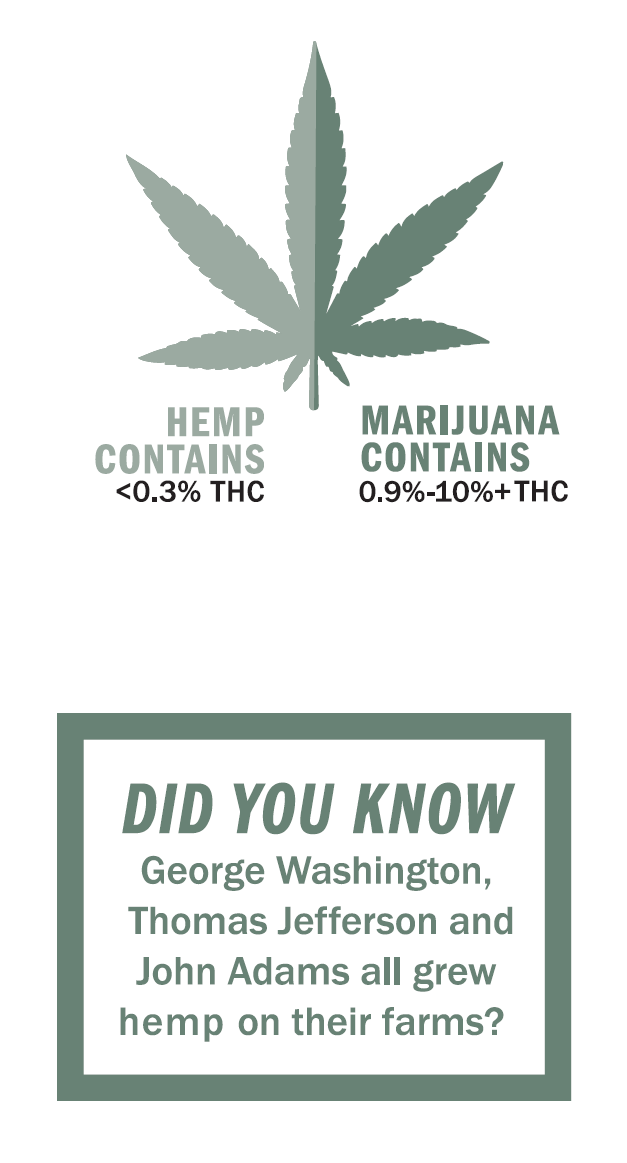

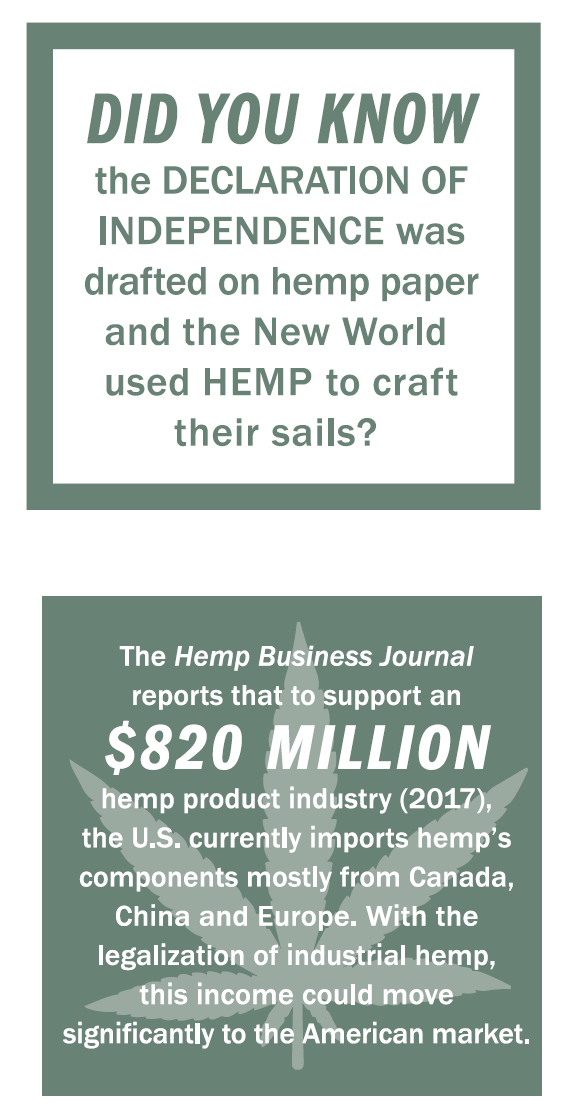

Hemp was an important crop in colonial America and some colonies were required by law to grow it. The Declaration of Independence was drafted on hemp paper and ships that sailed to and from the New World used sails and ropes crafted from hemp fiber. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams all grew hemp on their farms. In 1937, largely due to confusion with its intoxicating cousin (although many historians argue that paper manufacturing insiders used their political sway in support of the lumber-based trade), industrial hemp fell under heavy regulation in the U.S. with the federal “Marihuana Tax Act.”

During World War II, the “Hemp for Victory” campaign briefly halted this legislation. The initiative encouraged farmers to grow hemp and the crop’s fiber was crafted into rope and other textiles for the U.S. military.

Under the 1970s Controlled Substances Act and President Nixon’s war on drugs, all forms of cannabis were erroneously lumped together and banned, making industrial hemp illegal to grow, process or sell alongside marijuana.

ON THE HEMP HORIZON

Under the 2014 Farm Bill, or the Agricultural Act of 2014, state-level industrial hemp research programs were permitted if approved by a state’s legislature. A state’s department of agriculture or a higher-education institution, like Purdue University in Indiana’s case, was required to oversee these programs and expected to strictly control seed and ensure that all growers in the state were registered and monitored.

By the end of 2018, according to the advocacy group VoteHemp, 41 states had enacted legislation that made hemp production legal under specific circumstances. The group reports that in 2018, more than 78,000 acres of hemp were grown in 23 states.

Recently, Congress passed Section 10113 of the U.S. Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 (see page 41). Regarding hemp, the bill notes: “The term ‘hemp’ means the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of that plant, including the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

Congress’s use of 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, to classify the plant is crucial. THC causes cannabis’s famed high and has for the last 80 years been at the core of America’s confusion between hemp and its cousin marijuana. Both plants are varieties of Cannabis sativa L. and, although they look similar, they are different in their chemical composition due to their varied level of THC. The Purdue University Hemp Project explains on its website: “All Cannabis plants produce THC; however, marijuana contains high levels of THC (over 10%), and hemp contains very little (0.3%).”

The higher level of THC in marijuana can produce an altered mental state when the plant is smoked or consumed. It is virtually impossible, however, to get high on hemp. In their often-cited 2002 article “Hemp: A New Crop with New Uses for North America,” Ernest Small and David Marcus explain: “A THC concentration in marijuana of approximately 0.9% has been suggested as a practical minimum level to achieve the (illegal) intoxicant effect.”

In December 2018, the 2018 Farm Bill, or the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018, was signed into law by President Trump, federally legalizing industrial hemp by removing the crop from Schedule I of the nation’s controlled substances list. Industrial hemp is now recognized as a crop governed by the rules of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) rather than an illicit substance controlled by the Department of Justice.

The 2018 Farm Bill allows for broader cultivation of the plant beyond the state-level research programs permitted through the 2014 legislation. Cultivation of the crop is permitted through a heavily regulated federal-state structure where, among a range of other measures, crops must remain below 0.3% THC to be legal. Industrial hemp now also qualifies for a wealth of safety-net programs afforded to other commodity crops, such as crop insurance, access to federal grants and loans, as well as tax write-offs. Additionally, banks and other funders can open lines of credit to growers in the industry.

The federal action taken through the 2018 Farm Bill, however, does not immediately make an impact at the state level. “By the time the federal government made Cannabis illegal almost all states had already done so,” explains Erica McBride Stark, executive director of the National Hemp Association. “So this [the 2018 Farm Bill] is deconstructing Prohibition in reverse. The fact that hemp is no longer on the federal controlled substances list will not by default remove it from any given state’s controlled substances list.”

As a next step, states that have not already passed legislation to legalize the cultivation of industrial hemp within their borders will need to do so. Even the 41 states that have enacted some form of hemp legislation under the 2014 Farm Bill may need to revisit their laws as many were tailored to the research provisions in that legislation, McBride Stark says. If a state opts not to develop a program and the crop remains on the state’s controlled substances list, hemp cultivation will remain illegal in that state, she says.

“Who is going to build a processing plant in Indiana if it’s unclear if you can make money off of growing hemp? The 2018 Farm Bill helps to clarify that.”

A NEW MARKET FOR MIDWESTERN FARMERS?

In Indiana, Justin Swanson, a lawyer with Bose McKinney & Evans and vice president at Bose Public Affairs Group, expresses optimism that state government will pass updated legislation in 2019 in favor of industrial hemp cultivation.

“We have ambiguous statutes related to hemp production in Indiana,” Swanson says regarding the language passed by the state’s legislature after the signing of the 2014 Farm Bill. “We’ve had a grassroots movement since 2014 to help educate policymakers and other leaders in understanding what hemp is and what it is not,” he says.

Indiana has three entities working to advance industrial hemp: the Midwest Hemp Council, of which Swanson serves as president and which pushes on the policy horizon; the Indiana Hemp Industries Association, which focuses on product development; and the Hemp Chapter of the Indiana Farmers Union, which educates farmers. Since 2014, however, according to Swanson who cited Purdue University data filed with the Office of Indiana’s State Chemist & Seed Commissioner, Indiana has only grown 24 acres of the crop. Meanwhile, neighbors in Kentucky were licensed to grow over 12,000 acres in 2018, he says.

Kentucky has led the pack in hemp cultivation in Middle America as lawmakers and growers in the state took a keen interest in the hemp provisions of the 2014 Farm Bill. The Hemp Farming Act of 2018, eventually rolled into the 2018 Farm Bill as the legislation that led to the crop’s federal legalization, was an initiative of Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell. Kentucky has a robust history in hemp and McConnell faced pressure from growers, primarily from a dying tobacco trade, to revitalize the industry in his home state. Kentucky’s Department of Agriculture oversees the program and has invested extensive resources for monitoring production by a large number of growers in the state.

Meanwhile, in Ohio it remains illegal to grow the crop. The state starkly appears as an outlier on a map showing U.S. states that have legalized industrial hemp cultivation for research purposes. All the states that touch Ohio’s borders, not only Kentucky and Indiana but Michigan, Pennsylvania and West Virginia, have passed hemp-related legislation.

According to Joe Cornely of the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation, however, there is increased interest in industrial hemp from Ohio growers and at the group’s last business meeting in late 2018 the entity included the crop in its policy framework.

“When it comes to producing, processing and commercializing industrial hemp, we believe regulation is needed from the U.S. Department of Agriculture rather than the Drug Enforcement Agency. We also support federal legislation that would amend the Controlled Substances Act so that it specifically excludes industrial hemp,” Cornely said in December 2018, shortly after Congress passed the 2018 Farm Bill.

BUILDING UP THE BASE

In addition to legislative hurdles, a revived American hemp industry faces significant processing and infrastructure barriers due to its decades-long agricultural hiatus.

“The processing question has always been a chicken-and- the-egg thing,” Swanson says. “Who is going to build a processing plant in Indiana if it’s unclear if you can make money off of growing hemp? The 2018 Farm Bill helps to clarify that.”

The infrastructure shortcomings extend nationally. “We now have the legal framework in which to build an industry,” McBride Stark says regarding the most recent Farm Bill. “It’s really on the fiber side that we’re seriously lacking infrastructure and, ultimately, where I believe the majority of the hemp industry will lie,” she says. “That’s where the really large acreage is going to be grown when we start talking about supplying the auto and construction industries.”

Another significant question that remains is how much money can one actually make growing hemp. “Everybody is looking for an alternative to make more money per acre,” says Marty Mahan, a fifth-generation farmer who owns 200 acres in Indiana’s Rush County. Mahan serves as president of the Hemp Chapter of the Indiana Farmers Union. “Each week, community members reach out to me with interest,” he says of his role connecting with growers curious about the crop.

“What everybody wants to know is how much money they can make,” Mahan says. The U.S. does not have formal commodity pricing for hemp. “Right now, ballpark figures are that for growing for fiber you could clear $300–400 per acre, for seed $400–500 per acre and of course the big elephant in the room is CBD,” Mahan explains. (See sidebar on page 41.) “There is a significant amount of money that can be made in CBD. We’re talking five figures per acre. But harvesting for CBD is a whole different world unlike what farmers in Indiana are used to,” he says.

With 2019 poised for a fast and furious race for states to legalize the cultivation and processing of industrial hemp, many caution to not put all of one’s eggs in the metaphorical hemp basket.

“With the downturn in commodity prices, everyone is looking for an answer, myself included,” Boyer says. “Hemp has the potential to be a very exciting component and maybe a method of correcting the downturn in agriculture. That being said, the market needs to develop. We have a lot of infrastructure to build before we’ll ever see hemp as a widely grown commodity crop.”

Hemp Industry Growth in the U.S.

According to the 2018 “State of Hemp” report published by the Hemp Business Journal, in 2017 the U.S. hemp industry generated $820 million in sales, up 16% from 2017 despite operating in a relatively difficult regulatory climate. With $190 million in sales, CBD led the 2017 hemp market. The Journal notes, “The hemp industry was bolstered by explosive growth in the hemp-derived CBD category that grew from a market category that did not exist five years ago…” After CBD sales, hemp-derived personal care products generated $181 million in sales that year, industrial applications tallied $144 million and hemp-based foods accounted for $137 million. The remainder of 2017’s U.S. hemp-based product market resided in consumer textiles, supplements and “other” consumer products.

The publication projects that in 2018, the hemp industry in the U.S. would become a $1 billion market with continued steady growth. The authors write, “As legal and regulatory barriers are removed and consumer education spreads, Hemp Business Journal estimates the U.S. hemp industry will grow to a $1.9 billion market by 2022…” Other industry figures have been drastically more optimistic. For example, the Brightfield Group, a cannabis market-research firm, has projected that by 2022 the American CBD market alone will become a $22 billion industry.

To feed current market demand, “the U.S. remains the largest global importer of hemp products, which includes textiles from China, food and seed from Canada and industrials from Europe,” the Hemp Business Journal writes in their 2018 “State of Hemp” report. With federal legalization of hemp through the most recent Farm Bill, the American hemp market could shift significantly to U.S. production to feed this explosive market and, with this shift, hopefully America’s farmers would benefit handsomely.