Locally Grown Investment

Financing local, organic agriculture and its future sustainability

Despite a decade of rapid growth and increasing interest in sustainable agriculture and farmers markets, your local organic farmer may still have trouble obtaining the credit he needs to grow and prosper. What can the local community do with its investment dollars to support the kind of food system we want?

Saturday morning means farmers market. I rise with anticipation, gather my environmentally friendly shopping bags, and head on down to chat with and buy from local farmers. It’s the highlight of the weekend, this opportunity to purchase fresh, healthy, organic food, support my local farmer, safeguard my family’s health (we are what we eat!), and strike a blow against Big Ag.

But there is a worm in that organic apple.

The Bigger Picture

The worm is lack of investment capital to build and grow sustainable agriculture.

Small is beautiful, as E. F. Schumacher so memorably said, particularly when we see the small farmer as standing in heroic opposition to the harmful monocultures of Big Ag.

But could bigger, in this case, be better? Consider that only about 8% of food now purchased in the United States is organic. Adam Welly, owner of Wayward Seed Farm and a founding member of Great River Organics, a farmer-owned cooperative (GRO: see article on page 38), says that Kroger, Whole Foods, Giant Eagle, and other grocers with broad regional distribution have contacted GRO about providing locally grown organic produce because there is huge consumer demand for it.

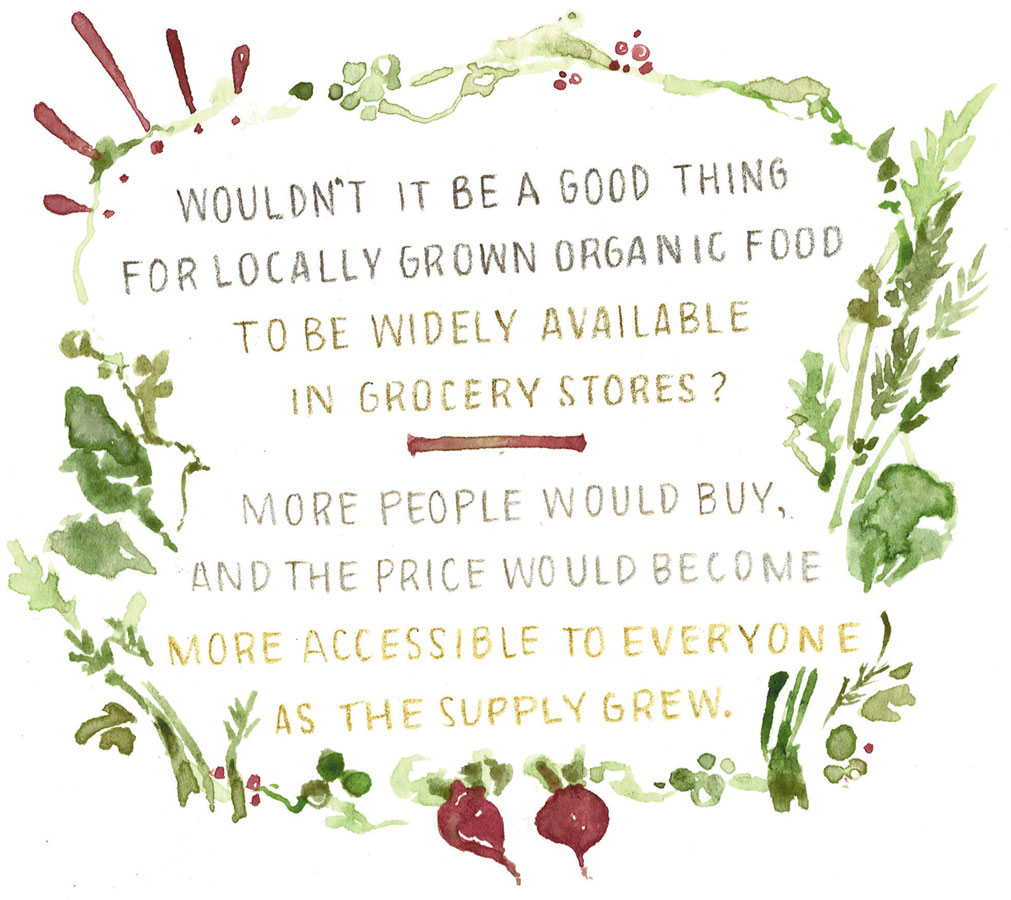

But, Adam says, right now our organic producers cannot grow enough to fill local shelves. Wouldn’t it be a good thing for locally grown organic food to be widely available in grocery stores? More people would buy, and the price would become more accessible to everyone as the supply grew.

To provide an organic alternative to conventionally grown farm products, organic farmers need to scale up to meet this demand. In this case, bigger can also be beautiful.

What a Farmer Needs

So consider the case of the small-scale organic farmer who wants to grow more organic food. What does that farmer need? According to Michael Jones, owner of Good Food Enterprises and a board member of GRO:

• Affordable land.

• On-farm infrastructure.

• Skilled, reliable labor.

• Business growth planning, marketing, and communication support.

• The expansion of market opportunities, especially wholesale.

But:

• Land in Ohio is expensive, and good farmland often goes to developers who will pay a higher price for it.

• Farm equipment and infrastructure are generally financed and paid off out of future earnings. A tractor costs $60,000 new.

• The Farm Safety Modernization Act, currently in the rulemaking stage, will mean more regulation, and therefore, more expense.

• Skilled farm labor deserves a good wage.

• Selling to retailers requires attention to food recall policies and procedures, food safety and commercial liability insurance.

• Product branding is another growth expense; if a farmer does not have the time or expertise to brand and market his products, then he must hire someone else to do it.

Clearly, a small-scale organic farmer who wants to grow needs access to affordable capital. Farming is capital-intensive, with the farmer generally spending most of the year preparing for the few income-producing months. Since so much of farming is forward-looking, farmers need equally forward-looking capital partners to back them.

Traditional Lenders are Leery of Organic Farming

If you can write a reasonable business plan and own a large, conventional farm that grows corn, soybeans, or grain, you can usually get a loan from a conventional lender like a bank, credit union, or farm credit bureau, because the investment risk metrics for conventional farming are well known to these institutions. Additionally, the Farm Service Agency (FSA), a department of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), extends loans to farmers who have been spurned by conventional lenders.

But banks and other lenders have less interest in small loans, and still less interest in supporting organic farming, which they perceive as risky. Due to the lack of risk data, crop insurance is also problematic. For example, when GRO member Dangling Carrot’s Becky Barnes lost a field of carrots due to flooding, the insurance adjustor paid her claim based on the market price of conventionally grown carrots, rather than the premium price of organic carrots.

The lending climate may change when organic farming has a longer track record. But what can the organic farmer do now?

Impact Investing

When conventional models don’t work, new models arise. Socially responsible investing has a long history—for instance, Quakers prohibited their members from investing in the slave trade. A more recent model is RSF Social Finance, a non-profit inspired by the beliefs of Austrian scientist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner. Since 1984, RSF has made more than $375 million in grants and loans in the categories of Food and Agriculture, Education and the Arts, and Ecological Stewardship.

Today we often speak instead of impact investing—investing that generates a social and environmental as well as financial return. Impact investing in agriculture is much more common in the West and the Northeast, but we in Ohio can look to other models and decide if we want to emulate them, or create our own, or both.

A paragon of impact investing is Iroquois Valley Farms. In 2007, the company created a private equity firm to buy farmland in the Midwest and lease it indefinitely to farmers who promise to farm the land sustainably. This model helps the farmer, since it takes three years to transition farmland from a conventional to an organic model, with no income in the meantime.

Managing Director of Business Operations Kevin Egolf cites two main factors for the success of the private equity firm: “indefinite ownership investment model and patience investors,” that is, investors who understand the model and “are not asking for a quick return or exit.”

“This allows the farmers to make long-term investments in soil fertility, leading to better yields and healthier food,” Kevin says. “This long-term approach is a win-win-win. The farmers have long-term land access, the environment is better off, and the investors get better returns on the investment.”

Closer to Home

In 1999, the Cuyahoga Valley Countryside Conservancy was created as a private non-profit to partner with Cuyahoga National Park. Countryside’s mission is to maintain the rural character of Cuyahoga County by allowing farmers to manage the land through sustainable farming, much like public land in Europe is leased to farmers to preserve and protect it.

In 2015, an additional two farms will be leased to join the 10 already a part of this successful program. Might a similar approach work with certain state parks in Ohio?

OEFFA (Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association), the non-profit responsible for the organic certification of Ohio farms, has made loan money available to qualifying organic farmers through the OEFFA Investment Fund and Zip Kiva. (See OEFFA website for details.)

Even the enterprising individual farmer can think outside the box to influence his financial destiny. GRO member Todd Schriver of Rock Dove Farms has created three- and five-year farm bonds for those who want to invest in his farm.

Slow Money Central Ohio

Created to encourage investors to find ways to invest in their local sustainable farmers, the nonprofit Slow Money has loaned more than $40 million to local food enterprises and organic farms since 2010.

Slow Money is a national but highly decentralized movement. Michael Jones is a member of the Slow Money Central Ohio (SMCO) steering committee working to develop the group’s goals.

In addition to matching sustainable investment opportunities with potential investors, he envisions educating the public about Slow Money’s aims. He adds that one of their goals is to match “more structured” community investment opportunities with “on-farm project needs that ultimately expand the organic supply chain.”

The Challenge and the Opportunity

Organic agriculture speaks not only of healthy food, but of healthy soil, air, and water; the preservation of family farms; the ability of farmers to earn a good living; and the ethic of giving back to the earth as a necessary component of receiving from it.

But lofty language is cheap, and action is needed. Do we the people of Central Ohio want the supply of sustainably grown food to substantially increase, until, as Ben Sippel of Sippel Family Farms and GRO says, “organic is the mainstream and conventional is the anomaly?” Then we need to ask ourselves, especially if we are people of means, whether we are willing to finance that growth.

“This is not philanthropy,” says Adam. “We’re legitimate businesspeople, and we want investment, because Ohio has great potential to be successful in creating a sustainable supply chain.”

Adam welcomes investment in GRO, and he also encourages organic farmers and would-be investors—including local credit unions, whose mission is rooted in community investment—to be “big, bold, and audacious” in considering new ideas and creating hitherto unimagined investment opportunities in sustainable agriculture here in Central Ohio.

In the language that comes naturally to a farmer, he urges readers and potential investors: “Let’s grow this thing!”

For more information about how you can get involved, contact Michael Jones at mjones@goodfoodenterprises.org; Slow Money Central Ohio at info@slowmoneycentralohio.org; and Great River Organics at greatriverfarms.org.