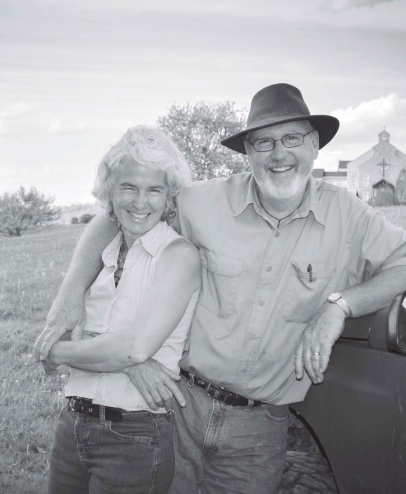

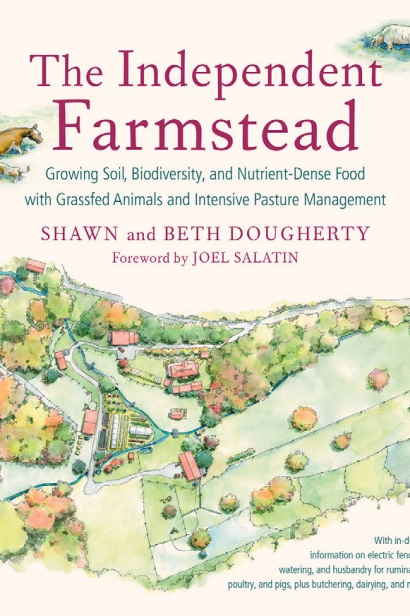

Q&A with Ohio's Shawn and Beth Dougherty, Authors of The Independent Farmstead

With a farm name like Sow’s Ear, it’s easy to wonder how a couple from eastern Ohio transformed a neglected, steep and rocky property into a productive one to feed their family of 10. Today, Shawn and Beth Dougherty blog, teach workshops and recently wrote The Independent Farmstead to share their 20 years of experience with the growing number of homesteaders.

Q: Tell us about your farm.

Shawn: We have one farm but two locations with a total 50 acres of grass. One farm is at the Franciscan convent where I also serve as their maintenance man. We run 25 of our cows there. A mile and a half away, we have the home farm with seven acres of grass where we run a dozen sheep, six pigs, four small calves and lots of poultry and have a large garden. The farm feeds the sisters and our family with dairy, vegetables and meat. We also run a small community dairy, called Two Sisters Creamery.

Q: Why did you decide to embark on this book project?

Beth: When we started out a long time ago, we were forging a new path and couldn’t find the books and articles to tell us what we needed to know. We spent a lot of time making discoveries. You know how it is when you make discoveries—you think “I wish I could tell other people. Like, here’s a mistake you don’t want to make.”

Q: From teaching classes, did you have a good sense of what your readers were looking for?

Beth: In class, our discoveries were always that books were giving scaleddown conventional methods for a home-sized chicken yard, garden or pigpen. Basically, here’s how many square feet to allow the animal and here’s how much feed to buy. We would get questions like “why this is so complicated?” and “how can I make this easier?” The answers are often simpler.

The snag goes like this: The farming methods we were looking for are the methods of our great-grandparents and great-great grandparents and were known and shared by everyone up until WWII. It was based on how the farm supported itself first, not how the farm created a product that is then marketable for money, and the money is spent to support the farm. Instead, we teach how the farm generates the nutrients that are necessary to keep that farm—all the animals, all the plants and all the people on that farm—before anything is exported.

Q: What are the top challenges small farms face today?

Beth: The number one obstacle for young farmers today, even before education and experience, is capital. We hear it over and over again, so we say “then don’t have capital.” Go find someone who is sick of mowing their yard—their acre and a half of fancy country lawn—and ask permission to care for it, put a temporary fence around it and run your animals there. There’s an awful lot of land going to waste or being pastured by somebody’s John Deere instead of a real animal.

Shawn: I think the top challenge is too much debt. You’ve got to find a way to do this without lots of equipment and without going into major debt to buy a piece of property. At an upcoming workshop at the Mother Earth News Fair, we’re going to be saying, “The piece of property that you think is the perfect piece of property is too expensive. So, settle for a junky piece and then make it good.” And, you don’t need tons of tools. We’ve done all our milking with no milking machine. We do it all by hand and buckets, and that saves us a lot of money. Our cows are all (fed) on grass, so our expense for feeding the cows is almost zero. We have to have fences to move them from grass to grass, but there is no grain.

In our case, the convent was close. People need to use properties that other people are not using, and work with them, and say “I can help feed you by using your property.”

Beth: Another challenge is when young farmers leap into a trendy farming niche like microgreens or shiitake mushrooms with the expectation that it will pay their bills. They don’t yet have sufficient experience, but they have all this energy, a bit of knowledge and a niche model. Many times the niche isn’t a good natural fit for the farm. They either fail and quit, or fail by compromising their initial farming motives so they can make money.

Q: What is your secret to successful farming?

Shawn: We feel the success comes from ruminants on grass and intensively moving these animals—we move ours every 12 hours to a new paddock. The good it does to the pasture is amazing, and the cows are doing well, too. (Shawn defines ruminants as “animals like cows, sheep and goats with multi-chambered stomachs that can digest roughage.”)

Beth: The secret to farming historically is “he who captures the most sunlight wins.” Since the biggest solar collectors on the planet are grasslands, we have to figure how to harvest those. Since people can’t eat grass, we use ruminants. The ruminants turn it into meat, milk, manure and more ruminants.

We like to tell people when they’re drinking milk, their food is yesterday’s sunlight. As we move our cows, they’re eating the most immediate access of sunlight—even more immediate than very fast-growing salad greens. Cows turn the sunlight into sugars, fats and proteins.

If you look at the successful farmers, whether Joel Salatin or Elliott Coleman or Allan Nation or Greg Judy, the ones who make the best use of sunlight and rainfall are the most successful farmers in the long term. “Successful” meaning, in the long-term sense, “as they use their farm, they’re improving their farm.”

Q: Are you encouraged by the growing interest in homesteading?

Shawn: Yes, and we’re especially evangelical about encouraging people to go out and get a cow. We hear all this talk about eating organically but wonder what those people do for food. How do those people get really nutritional food? And, the only way to do it is find a farmer who’s doing it, or do it yourself. And, for those people that think the notion of having a cow or pigs or chickens is so far out there, it’s not. It’s doable.

Find the The Independent Farmstead at Chelsea Green Publishing, and learn more about Beth and Shawn’s farm at onecowrevolution.wordpress.com.