The Soil Scientist: Ohio State’s Rattan Lal Wins Global Recognition

“The honor means so much to me,” Rattan Lal says humbly several months after being named the 2020 World Food Prize Laureate. He is a distinguished university professor of soil science at The Ohio State University’s College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences and the founding director of the university’s Carbon Management and Sequestration Center. “I honestly could not imagine that I would get the World Food Prize.”

In June he became the 50th recipient of one of the most distinguished global prizes in agriculture. He is the fourth soil scientist to receive the recognition.

However, this is not the first prestigious honor for Lal, a prolific scientist who has studied the Earth’s soils for more than five decades and who is recognized as a top expert in the field. In recent years, he has been given the Japan Prize, the World Agriculture Prize and the Glinka World Soil Prize. Lal was also a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, an entity that shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore.

Lal’s research spanning four continents focuses on a soil-centric approach to increasing the quantity and quality of food produced for human consumption. His work has questioned agriculture’s dependence on commercial fertilizers, showing that the cultivation of crops on healthy soil managed naturally creates a greater abundance of food while using less land, fewer agrochemicals and less energy and water—all net benefits.

Lal has studied the power of soil as a tool to sequester carbon, a groundbreaking finding that has been embraced by a slew of experts as essential in mitigating climate change. Research that he co-authored in the 1990s was the first to demonstrate that atmospheric carbon can be sequestered through the restoration of degraded soils. This finding has been monumental in the world of climate-resilient agriculture in an industry challenged by the climate change debate.

Dr. Lal works with a student at OSU’s Western Agricultural Research Station in Clark County. (Photo courtesy of Ohio State University / Ken Chamberlain)

The World Food Prize, announced in an online ceremony in June, includes a $250,000 award. (Photo courtesy of World Food Prize)

“When soil quantity and health is satisfactory and appropriate for plant growth, produce for human food will also be high quality,” Lal explains. He calls this “nexus thinking,” or a focus on the interconnectivity of soil, plants, animals and people, as central to a healthy ecosystem. “If the health of soil goes down, the health of animals, people, and the environment goes down,” he says about this interdependent web of life.

For this reason, Lal has been a vocal advocate for a soil quality act in the United States—much like the clean air and water acts formulated in the 1960s and ’70s. “How is it ever possible to have clean water and air without healthy soil?” Lal asks. He points to the now-annual presence of algal blooms on Lake Erie’s shoreline, which are mostly attributed to agricultural runoff from the resource’s rural watershed.

Lal says he wants to see policymakers incentivize farmers for adopting practices that protect and benefit the soil. “The solution lies in management of the soil surface so there is no runoff from rainfall, snowmelt or the application of fertilizer or manure,” he adds. “That means making sure the soil is always covered by live roots, that it’s never plowed, that it has a cover crop grown in the off-season.”

Lal was raised on a five-acre farm in rural India where planting and harvesting were manual. He says his childhood observation of the natural world around him spurred his lifelong interest in soil, the bedrock of life on his family’s small agricultural operation. Lal calls himself incredibly lucky as a boy from a rural village to have the opportunity to attend college, an honor his siblings were not afforded.

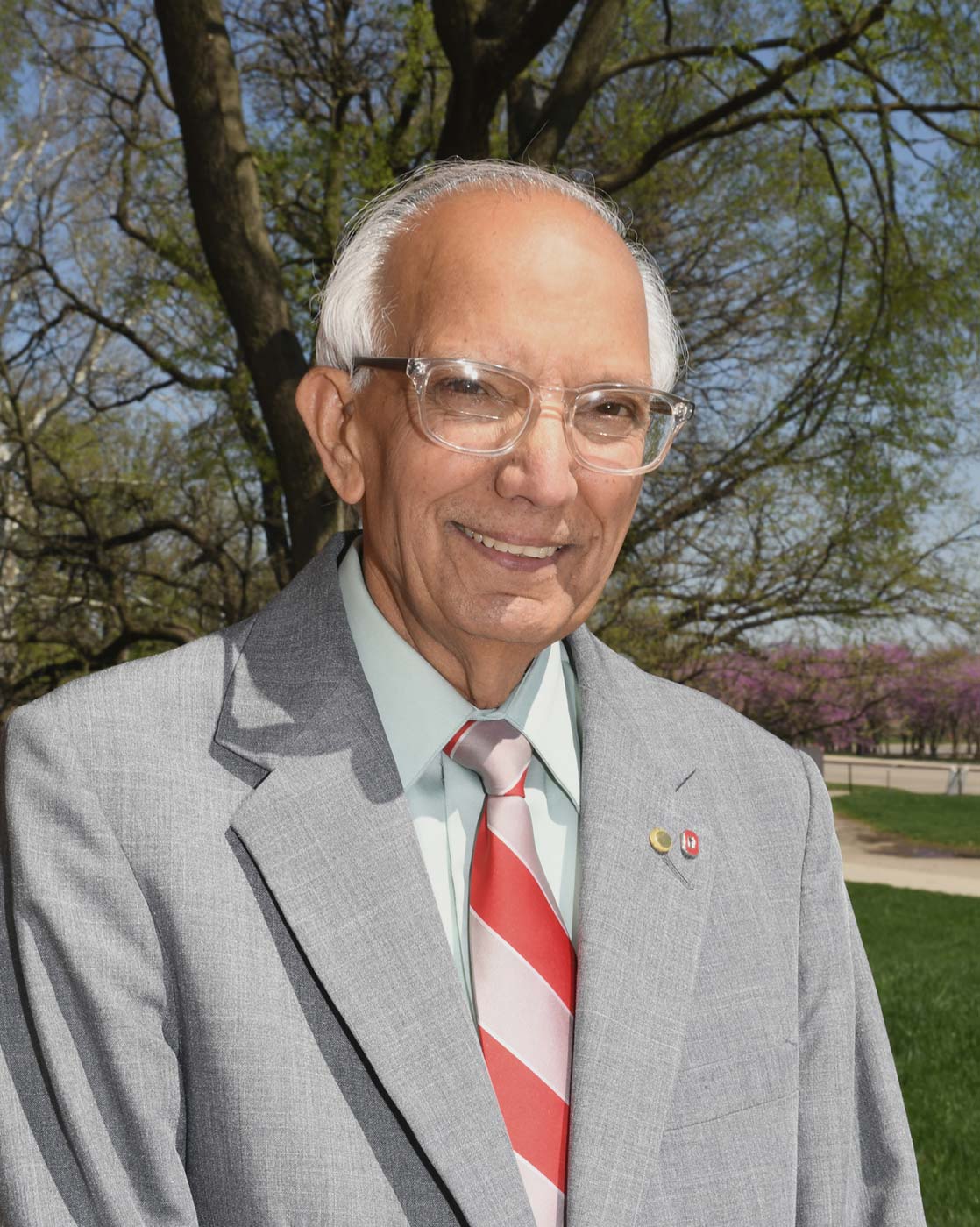

Dr. Lal has been based at Ohio State for the last 30 years. (Photo courtesy of Ohio State University / Ken Chamberlain)

Some of the professors who taught him at Punjab Agricultural University had recently returned from their own studies at Ohio State. “I was fascinated when they would show us pictures of Ohio,” he says. “Columbus, Wooster, Thompson Library. I thought, ‘My gosh, I wish I could go there.’ And I did,” he says about completing his PhD at the university in 1968.

Lal returned to Ohio in 1987, this time as a faculty member at Ohio State. Despite his worldwide recognition and vast research experience across the globe, the humble academic says he feels “privileged and fortunate” to have called the university his home for the last 30 years. “I genuinely feel that having the stamp of Ohio State next to my name is a major factor in me getting these awards,” he says about honors like the World Food Prize, which includes a $250,000 award. Lal has donated most of the money bestowed upon him through the prizes back to the university as an endowment for the Carbon Management and Sequestration Center, enabling its research to continue beyond his years as the program’s lead.

And after more than 50 years in the profession, the soil scientist says the most important lesson he’s learned over the decades is that his discipline must be taught more prominently in elementary education to ensure future generations prioritize and protect the world’s soils.

“Each student must know that soil is the basis of life,” Lal says. “The ancient civilizations—the Mayan, Aztec, Incas, Mesopotamians—they perished because they ignored the health of the soil. Our civilization will be in serious jeopardy if we follow this path.”

- Learn more about Dr. Lal and the center he founded at cmasc.osu.edu. Details about his latest honor are at the World Food Prize website.