Pandemic Brings Changes To How We Shop For Food

If there is one element of pandemic precautions that has affected everyone, it would be changes in how we shop for our food. When restaurants, schools and businesses were shut down, grocery stores saw an immediate spike in demand—and a spike in concern about how to keep both customers and employees safe. On a trip to the store today, you likely will face shortened hours, some product shortages, employees wearing masks, and stickers on the floor to assist in social distancing.

Meanwhile, a favorite summer activity for many food lovers is a visit to an outdoor farmers market, moving through the crowd, going from table to table to pick out fruits and vegetables and other products from the vendors. But when the markets opened—if they opened—for 2020, new rules were in place to keep everyone safe if not always happy.

Here are stories of how shopping has changed in our community.

Weiland’s Market has been serving Clintonville for nearly 60 years. Photo by Edible Columbus.

WEILAND’S MARKET: ALL FOR ONE, ONE FOR ALL

“It’s like trying to change a tire while driving down the highway at 65 miles an hour,” says Jennifer Williams when asked what it’s like to navigate a global pandemic as an independent grocer.

Jennifer and her husband, Scott Bowman, are the current owners of Weiland’s Market, after taking over in 2011 from Jennifer’s father, a third-generation grocer. For the uninitiated, Weiland’s is an independent grocery store in Clintonville, yet Jennifer jokes that it feels more like a co-op some days.

In the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, when supply chains were stressed and common food items were suddenly nowhere to be found, the question arose whether smaller independent grocery stores like Weiland’s would be able to meet the demands of the community—especially without the resources of big-box chain stores. And could they keep their community safe while they shop? And what about their own employees? Could they keep them safe too?

As it turns out, not only has Weiland’s risen to the challenge, it’s thriving. Three elements are apparent in making this so.

First, certain advantages come with independent ownership, like the ability to make decisions quickly. From the beginning, Jennifer and Scott have proven to be agile. They swiftly implemented new safety measures, such as installing plexiglass shields at checkout lines, ceasing in-store sampling, limiting the number of shoppers, and providing staff with masks to wear and encouraging shoppers to do the same.

Second, in times of hardship we as humans have often turned to food for comfort as well as nutrition. Recipes can seem like a soothing balm in times of stress and uncertainty. Jennifer says books like Sarah Black’s One Dough, Ten Breads have been flying off the shelves, so much so that she even set up a quick ingredient station to make it easy for customers to grab and go. With restaurants closing and orders for sheltering in place, many of us have rediscovered our kitchens.

The third element that has allowed Weiland’s to thrive, and perhaps the most important, is its community. Weiland’s has been family owned for just shy of six decades and is very much part of the fabric of Clintonville, interwoven with local farmers and suppliers, independent makers and, of course, the neighbors themselves.

When fellow independent stores began to struggle, Weiland’s became a model of mutual support by offering pop-up spots in the store for small businesses like Wild Cat! Gift store and Colonial Candy. And to help ensure the safety of the community, Weiland’s has also begun selling masks sewn by local residents. This success, however, hasn’t been met without immense hardship.

“It feels like it’s been years since this started,” not just a few months, Jennifer says. She is very well aware of the emotional, mental and physical toll the pandemic is taking on her employees. She’s made adjustments where she can, like shortening store hours so employees can have time alone to stock items and decompress.

When asked how they manage to keep going, her response was, “because of the community.” Words of encouragement from customers in the store and on social media have meant the world to them, as well as small gestures like returning carts.

While it may not have the resources of a larger chain store, Weiland’s feels like an all for one, and one for all effort. And while we can’t hug one another—yet—there’s something comforting about a group of people who show up every day for their community, with smiling eyes behind a mask.

—Malinda Meadows

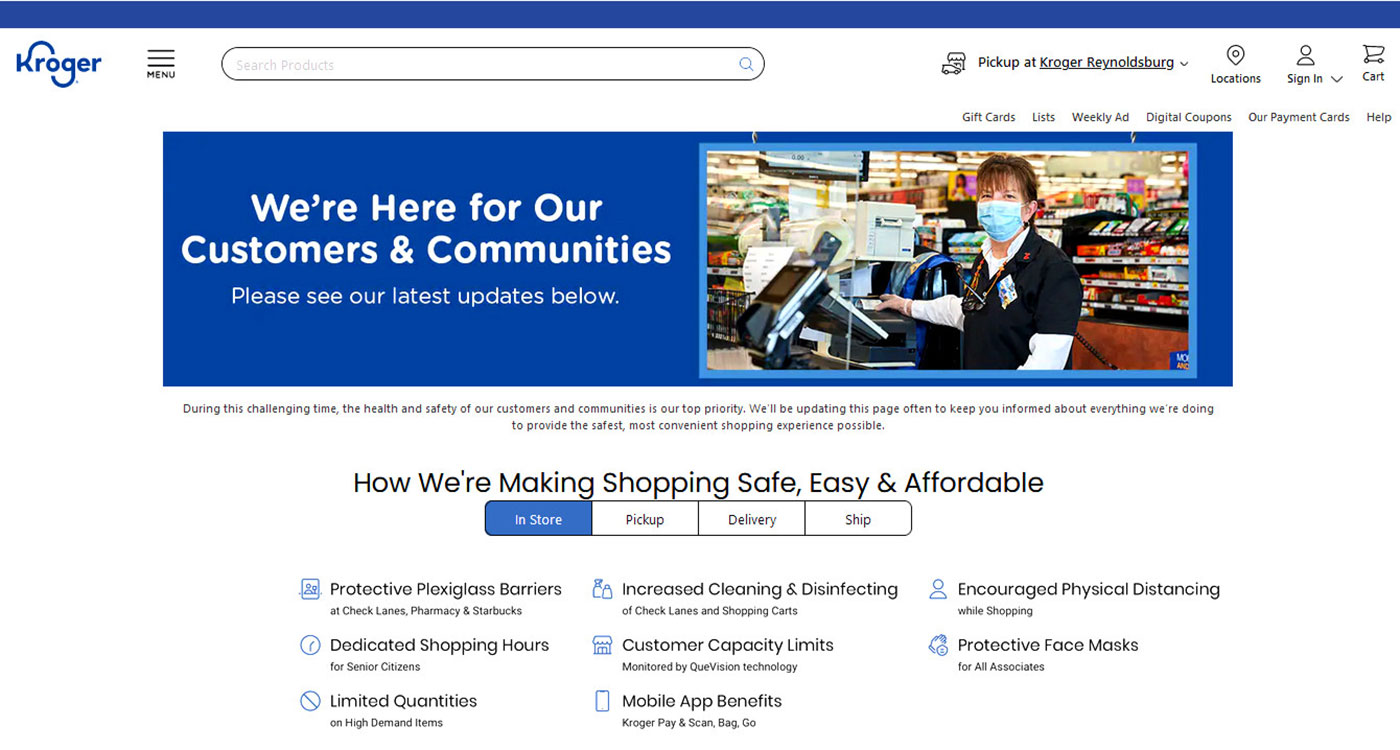

Kroger used its website to keep customers around the country informed of changes being made in the stores.

KROGER: BIGGEST IN THE LAND

At the other end of the spectrum from a small, independent grocer is Kroger, the largest grocery store chain in the country, with about 2,700 stores. In Columbus and the surrounding counties, the chain has more than 50 stores with a total of 10,000 employees. When it comes to grocery shopping, Cincinnati-based Kroger is the big dog, with more of everything.

In a pandemic, that means more demand for groceries, with a 30% surge in sales just in March. It also means more product shortages, with toilet paper and cleaning supplies wiped out in the early days, and meat following shortly behind. And it means a bigger challenge in trying to keep and hire employees while also making stores safe for shoppers.

In a series of emails to customers, Kroger CEO Rodney McMullen identified steps the company took, including requiring employees to wear masks, adding plexiglass partitions at checkout lanes, limiting the number of people in a store, and adding hours for seniors and other vulnerable populations. Kroger also made its curbside pickup service free, although customers quickly overwhelmed the system, resulting in long delays.

Meanwhile, Kroger hired 100,000 new employees in eight weeks, providing jobs for those who lost work in the hardest-hit sectors like restaurants, hotels and bars. All employees got a $2 per hour pay increase, later converted to a monthly “Hero Bonus.”

Always a strong supporter of food banks and charities, Kroger launched an Emergency COVID-19 Response Fund, committing $7 million in hunger relief grants and purchasing 200,000 gallons of milk from farmers to donate to food banks.

“While we don’t know what the future brings, what I do know is that our team is capable, prepared and resilient,” McMullen wrote to customers in May. “We’ll continue to adapt and adjust to do what’s best for each other.”

—Gary Kiefer

The Clintonville Farmers Market switched to a drive-thru model at the Ohio History Center. Photo by Edible Columbus.

Pre-ordered items are packaged and awaiting pickup at the Clintonville market. Photo by Edible Columbus.

CLINTONVILLE FARMERS’ MARKET: ADAPTATION IS KEY

“It’s been a blur,” says Michelle White, manager of the Clintonville Farmers’ Market, about the marketplace’s swift transition to a pre-order, drive-thru model in the early weeks of the 2020 growing season due to COVID-19. “I feel like the past few weeks have been an entire year,” she adds with a chuckle.

The arrival of the coronavirus in Ohio—and the corresponding rapid shutdown of the state—aligned with the kick-off of the farmers market season across the region. Deemed an essential business—much like grocery stores and pharmacies—these markets and their vast network of vendors were spared but had to quickly pivot to enact new ways of working in the face of social distancing.

At the Clintonville market, the season launched with a pre-order, drive-thru operation in the vast parking lot of the Ohio History Center near the I-71 freeway. “We didn’t feel comfortable operating a walk-up market on High Street,” White says about the tough decisions facing her and the market board in the early days of the pandemic. “There’s just not the opportunity to do any type of traffic control, not to mention with social distancing we’d only be able to allow 19 vendors,” she says. On a typical Saturday last year, an average of 53 vendors filled the street.

White and her team decided to transition their vendors’ products to an e-commerce site called Local Line. The effort was not without complications. In the early weeks of utilizing the resource there was a constant stream of customer complaints about order wait times and website freezing.

“We decided to adopt a centralized sales platform to make it as easy as possible for customers to shop,” White explains. “In hindsight, it’s a lot of work for market staff to manage all sales. But I think our producers have been happy with the results,” she says of the nearly 40 vendors who participated in the pre-order, drive-thru market in the early weeks of the operation. White adds that at the start of the season, sales at the drive-thru consistently matched those of years prior when the market operated on High Street.

However, as the season progresses and more product becomes available, White and her board grow increasingly concerned about the ability of the drive-thru model to keep pace with demand. “We’re committed to the drive-thru concept for eight weeks,” White says. “But we’re discussing the transition. The drive-thru model requires an exorbitant amount of staff time. The sooner we can go to a hybrid model the better.”

In a hybrid format, the market hopes to offer shoppers two options. One would be the pre-order component, which some customers—especially those particularly vulnerable to COVID-19—have expressed a preference for. The second would be a socially distanced walk-up market with controlled entry points to ensure the number of customers participating matches state and federal guidance. At the time of publication, White says the location of this hybrid and whether it will continue at the Ohio History Center’s parking lot is still uncertain.

Regardless, despite the stress of the current moment and the heaviness of formulating what lies ahead, White says she and her team have learned significantly as a result of the health crisis. “A silver lining is that it pushed us to think about the possibilities of a different type of sales model,” she says. “We’ve been tossing around concepts,” she says about her board and their observation of a growing consumer preference for home delivery and pre-packaged product. “I think pre-order platforms are moving farmers markets forward, which is exciting.”

—Nicole Rasul

OTHER MARKETS, OTHER FORMATS

The city’s most famous—and only year-round—public market is the downtown North Market, which was hit hard by the pandemic. Early on, the market closed off its mezzanine dining area and the majority of the 30 vendors shut down for a time. Some continued to offer food bundles that could be ordered online and picked up once a week. By the end of May, more than 20 vendors were back in business in some form, with both employees and customers required to wear masks.

The Worthington Farmers Market, which operated an indoor winter market, shut down in mid-March and later switched to an outdoor drive-thru concept. Customers were provided a list of vendors and required to order from and pay the vendors directly. Orders could be picked up on Saturdays at Worthington Community Center. The popularity initially caused long lines of cars as volunteers scrambled to meet the demand. But Market Manager Christine Hawks and her crew were pioneering a concept that would be followed by farmers markets in Grove City, Clintonville and elsewhere.

Markets that are offering a traditional walk-up experience this summer have several things in common: a move to larger spaces to spread out vendors, social distancing rules, no pets allowed and masks required for all. Falling into that category are the markets in Bexley, Canal Winchester, Granville, Hilliard, Pickerington, Reynoldsburg, Upper Arlington and Westerville. The Pearl Market downtown also offers walk-up shopping, but recommends ordering online in advance.

Both the Dublin Market and the New Albany Farmers Market delayed their openings to figure things out.

At least two locations— Franklin Park Conservatory and Uptown Westerville’s Market Wednesday—decided to cancel their 2020 summer markets.