A Wild Spring: One Cook's Hunt for Morels, Ramps and More

The snap of a twig, the rustle of the dead leaves beneath my boots, break the silence as I move slowly down the hill’s slope, using small saplings to help keep my balance. The anemic breeze still carries the bite of winter, but the golden warmth of the spring sun streaks through the leafless canopy, making up the difference.

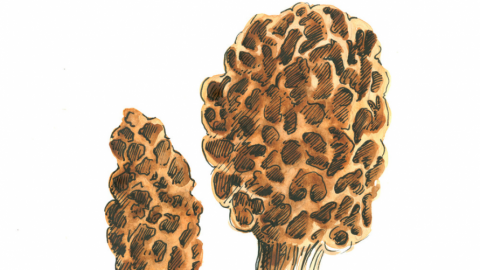

Searching through the understory debris, in the shade of a large tree, I see it—a three-inch brown, honey-combed, conical looking sponge pushing up through the soil—the most beloved of all wild mushrooms, the morel. I yell, “Mushroom!!” as loud as I can and my companions come running, because we all know where there is one, there will be more. The hunt begins.

Though we spent that afternoon in Fallsburg, Ohio, an hour out of the city in Licking County, morels can be found from early April into May, just after the second deep spring rain, right about the same time the Eastern Redbud trees start to produce their blooms. And while organic groceries, farmers markets and home gardens are all great sources for dinner ingredients, one of the best food adventures you can have is bringing a bit of wild nature back to your own kitchen.

Though you can find ingredients to use any season, spring is the best time to find the most tender and succulent ingredients. Wild plants tend to either fade quickly or harden as the weeks move on into summer and autumn. For example, a red-veined sorrel is citrusy and tender in early spring, ready to brighten any dish, but becomes unpalatable, more bitter and tough as temperatures rise in early summer. The same is true for wild asparagus. If you do not cut them as newly sprouting shoots, you will soon lose them to the more mature fern-like shrub form that is nice to look at, but is not edible.

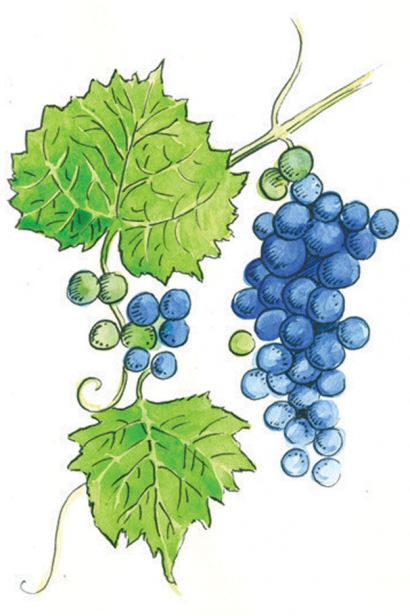

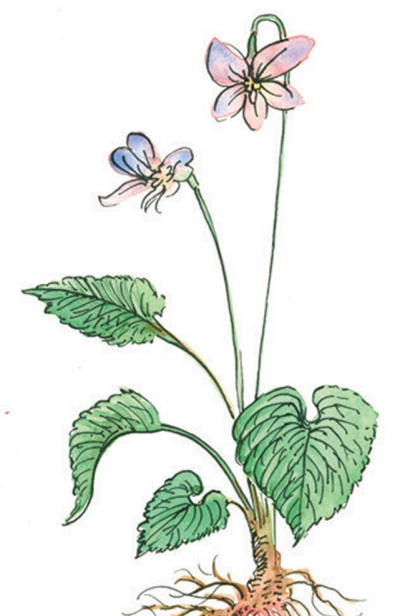

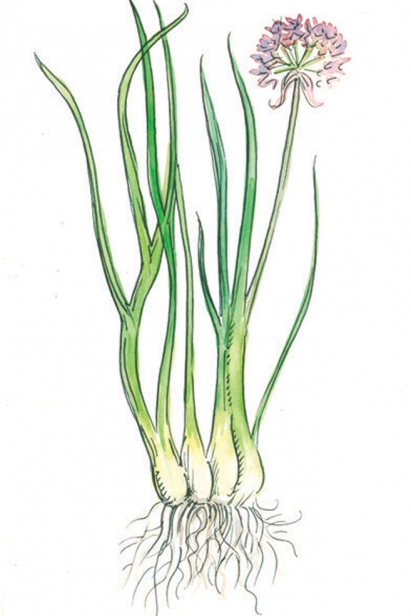

You will be surprised by what is available for you to find very close to your own home. We live in a wooded area north of Westerville and within my own yard, I have used fern fiddleheads, oyster mushrooms, dandelion greens, wild onion and garlic, red-veined sorrel, wild grape, wood violet, wild mint, wild black raspberry, sassafras, wild rose hip and black walnut in dishes I have prepared.

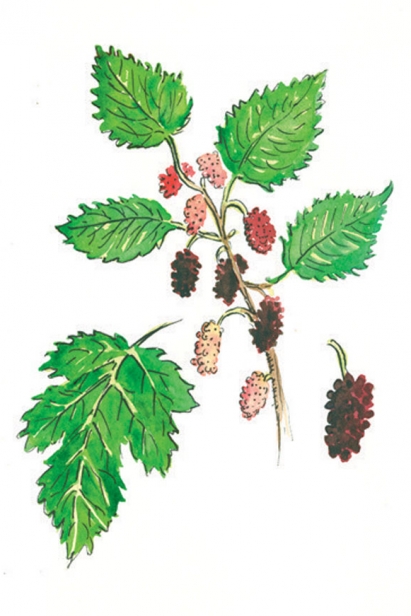

Our beloved morel mushroom is sold in stores at $40 per pound when in season. A mile down the road from my home I can pick mulberries in early June. I have never found mulberries in any market here, perhaps because of their short shelf life, yet they are plump and uniquely and sweetly delicious, rivaling any berry commercially grown. They would be delicious in a galette or served in their own juices with a spiced sabayon. The ramp, a wild garlic, has landed on many a bib gourmand restaurant menu in recent years. Foraging for wild edible foods is truly like culinary treasure hunting.

As a child, I remember my mother sending me out into our backyard to collect dandelion greens. At the time, I thought she was joking. Who eats weeds for dinner? Now we see them commercially grown and in almost all of our local groceries. But even at age 9, I knew what a dandelion looked like—find the flower, find the leaves, simple.

Now foraging for wild ingredients can be intimidating and learning some basic plant identification is recommended. There are many resources available to get you started and the rewards are worth the effort.

You already likely have some basic foraging knowledge. More adventurous foraging, like wild mushroom hunting, carries slightly more risk than dandelion identification. That’s where good solid resources come in, like The Ohio Mushroom Society, or go with an experienced hunter. Another one of my favorite resources is the book, Edible Wild Plants—A North American Field Guide to Over 200 Natural Foods by Elias & Dykeman. This field guide is well organized by season and easy to use with color plates for each plant. It covers appropriate harvest times, habitat, differentiation regarding toxic look-a-likes and even preparation tips, keeping the novice out of trouble. Start Mushrooming—The Easiest Way to Start Collecting 6 Edible Mushrooms by Tekiela & Shanberg is another one I like.

As a rule of thumb, I do try to avoid plants that have an increased risk of health consequences. For example, ground cherry might be great for a fruit pie, but should only be harvested when the fruit is absolutely ripe; otherwise, it can cause some gastrointestinal toxicity. That’s a grey area that I try to avoid. Learn to find a few wild ingredients that you are comfortable identifying, know when to search for them and how to safely prepare them, and then enjoy these gifts from nature.

When you get back to your kitchen, try to use your new foraged ingredients in your cooking as you would anything you may get from the markets. You don’t have to hide them in a dish (they taste good) or figure out how to make them the focus (they taste good with other things). Don’t be intimidated when your best friend refers to your treasured ingredients as “lawn clippings.” Respect the wild ingredient for what it offers to your dish. You will find sweet, fruity, peppery, bitter, nutty and citrus notes in many of these natural foods, which makes them quite versatile.

For me, springtime represents freshness and simplicity and that is how I like to use the wild spring ingredients I find. My recipes can be made for a springtime brunch that will really reconnect you and your brunch guests back to nature. Good hunting!